A major power line collapse at Strathfield has paralyzed Sydney’s train network. The crisis began at 2:30 PM Tuesday when a train’s power collector became entangled with a 1500-volt overhead wire, trapping 300 passengers and triggering widespread power outages across six major train lines.

Repair crews battled through Tuesday night’s rain, but the damage runs deeper than broken wires. Trains are currently running four to five times slower than usual. Regular service won’t return until Thursday morning, forcing commuters to find alternative routes.

“I spent $100 on taxis,” says a teacher from the Central Coast who faced severe delays on the T9 line. “The real problem isn’t just today’s delays – it’s that these breakdowns keep happening.”

The numbers tell the story. Trains are running with wait times of around 20-30 minutes between services across the city. The Sydney Metro, while operating normally, is now packed with displaced train passengers. At Lidcombe station, commuters like Ben U’Brien waited an hour for replacement buses, with many passengers left stranded in the rain.

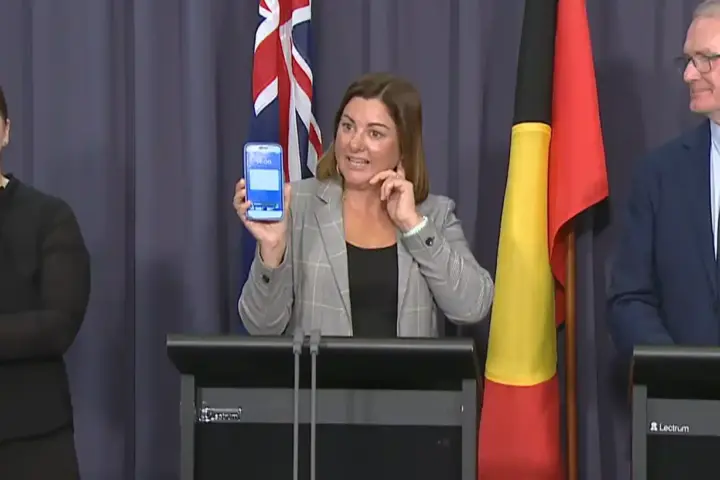

Premier Chris Minns announced a fare-free Monday for train and metro users, but commuters say it barely covers their extra transport costs. Even with surge price controls in place, Uber costs increased significantly during the crisis.

Similar Posts

Transport Minister John Graham revealed the collapsed wire had passed inspection on April 9. This admission raises serious questions about maintenance standards. The government’s response? A new independent review focusing on three critical areas: maintenance programs, train punctuality, and emergency communications.

For businesses, the cost multiplies. Ben U’Brien, a public servant, left Bathurst at 3:30 AM for his usual three-and-a-half-hour commute to Sydney. He arrived seven hours later, missing crucial morning meetings. Multiply this across thousands of workers, and the economic impact becomes clear.

The timing couldn’t be worse. Vivid Sydney starts May 23, and authorities expect train services to be fully restored by then, given the festival’s importance to the NSW Government.

Behind the immediate crisis lies a broader problem. Sydney’s rail network runs on infrastructure that’s showing its age. The 1500-volt power system struggles to meet modern demands.

Emergency measures are in place: limited bus services run from Hornsby, Penrith, and Campbelltown. The T4 Eastern Suburbs and Illawarra Line remains the only route running a normal timetable. All other passengers face a maze of partial services, replacement buses, and station changes.

The human cost is evident in stories like Reena Yadav’s. Her commute from Quakers Hill turned into a four-hour journey, ending with an $80 taxi ride to Randwick. She missed an important work event, joining thousands of others whose daily lives have been upended.

This isn’t just about trains running late. It’s about a system that’s failing the people who depend on it. As one commuter from the Central Coast put it: “For a world city, our network can be quite unreliable. When there are issues, it can take hours to actually get anywhere.”

Transport authorities promise better communication and more replacement services. But for Sydney’s commuters, forced to navigate this crisis with limited information and fewer options, these promises ring hollow against the reality of another day of chaos on the rails.