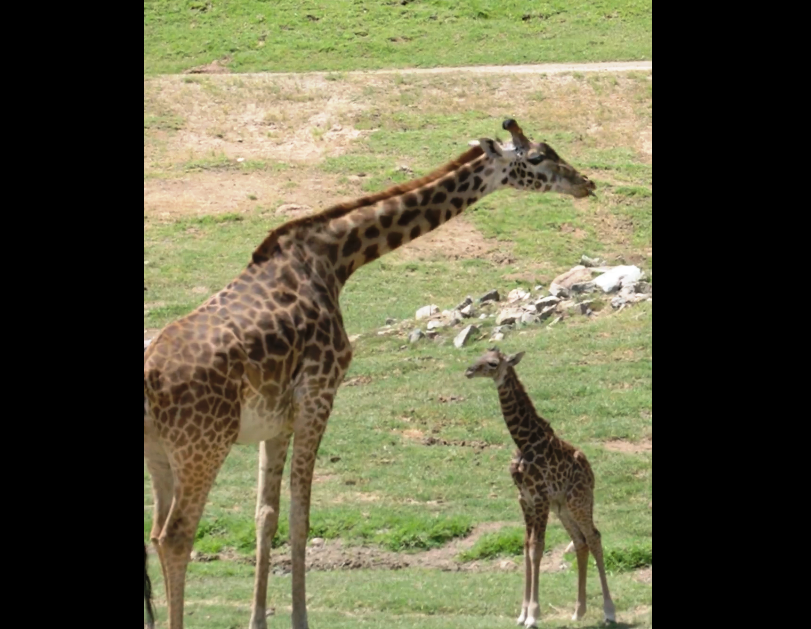

A male Masai giraffe calf wobbled into existence on April 23 at San Diego Zoo Safari Park, born to mother Mara and father Gowon. This spotted youngster, while undeniably adorable with those gangly legs and curious eyes, carries enormous weight for his species’ future—genetic gold for a population plummeting in the wild.

The calf and Mara currently hunker down apart from the herd, not from antisocial tendencies but following ancient maternal instincts. This natural separation allows critical bonding before the pair rejoins their towering collective. Keen-eyed visitors might spot this maternal masterclass happening now in the South Africa habitat at the park.

Masai giraffes lumber under the heavy “Endangered” classification from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Wild numbers have nosedived by a gut-wrenching 52 % over three decades, with merely 32,550 mature individuals remaining in central/southern Kenya and northern Tanzania; their iconic patchwork coats, once abundant across East African savannas, grow increasingly scarce as habitat fragments are being lost beneath human expansion (Giraffe Conservation Foundation).

The calf’s arrival bolsters the Association of Zoos and Aquariums Species Survival Plan (SSP)—a genetic lifeline aiming for over 90 % gene retention across a century of breeding. Each carefully planned birth weaves essential genetic diversity into the captive population’s tapestry.

Giraffe pregnancies stretch a marathon 15 months, after which calves typically stand within their first hour—an evolutionary necessity when predators lurk. The initial 24-hour mark peak vulnerability, with mortality risks substantially higher in wild settings than under watchful zoo care.

The taxonomic journey of Masai giraffes traces back to 1898 when zoologist Paul Matschie described the subspecies, naming it after Baron von Tippelskirch’s specimen. Recent genetic studies stir scientific debate about whether giraffes represent multiple species rather than a single species with subspecies, taxonomic questions potentially reshaping conservation strategies.

Beyond zoo walls, wild Masai giraffes face a gauntlet of threats: habitat bulldozed for agriculture, poaching for meat and traditional medicine, clashes at human settlement boundaries, and climate change altering food and water availability. Localized giraffe skin disease adds another challenge for Tanzanian populations (Wild Nature Institute).

Conservation efforts by multiple organizations include anti-poaching units, community education programs, corridor protection between fragmented habitats, and restoration projects. Research demonstrates increased calf survival where community conservation programs operate, particularly at protected area boundaries.

Every spindly-legged calf born under managed care sends ripples of hope through conservation circles. While challenges loom as large as the giraffes themselves, collaborative efforts between zoological institutions, field organizations, and range countries offer narrow but viable paths toward stabilizing populations of these gentle giants.

The tallest chapter in Earth’s mammalian story struggles to stay upright—each successful birth represents another page rather than an ending.