A smartphone in your pocket could help uncover species not seen for over a century. This isn’t science fiction – it’s happening right now through the power of citizen science.

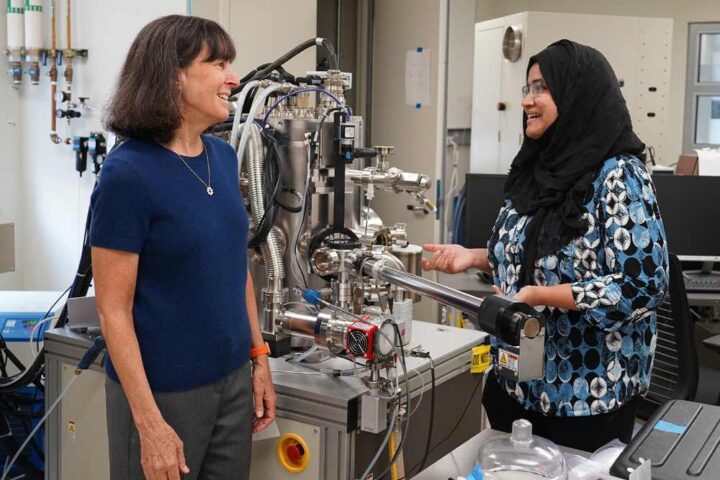

Researchers from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Sydney have measured the growing impact of iNaturalist, a platform where anyone can upload photos of plants and animals they spot in the wild. Their findings reveal how ordinary people are revolutionizing biodiversity research.

The study, published in the journal BioScience, shows that scientific papers using iNaturalist data have increased tenfold in just five years. This explosion matches the growing number of observations being uploaded to the platform.

“With cameras and smartphones now everywhere, just about anyone can use iNaturalist to record living things anywhere in the world,” explains Simon Gorta, a PhD candidate at UNSW and co-author of the study. “Our research shows that the abundance of data this process generates is driving important biodiversity research.”

The impact is already clear. In one striking example, the Angled Australian Barkhopper, a tiny grasshopper measuring only one or two centimeters, was rediscovered after being missing from scientific records for more than 130 years. Citizen scientists in northern New South Wales and Queensland photographed the insects and uploaded the images to iNaturalist, where a European expert identified them.

Similar Posts

Since its launch in 2008, the platform has collected impressive numbers: 262 million observations of 518,000 species recorded by 3.8 million observers worldwide. In Australia alone, 121,000 people have submitted 11.5 million observations covering over 64,000 species.

Scientists are using this wealth of information for numerous purposes beyond identifying new or rare species. The data helps researchers understand where species live, plan conservation efforts, model habitats, track climate change impacts, and manage invasive weeds.

“Time and money are precious resources which seem to be increasingly dwindling,” notes Thomas Mesaglio, another study co-author and PhD candidate from UNSW. “What iNaturalist does is massively expand the monitoring network to millions of people around the globe.”

This expansion proves particularly valuable when researchers need to locate specific species in large areas with limited resources. “Need to find a particular species in an enormous search area but have limited time and resources? You can check iNaturalist records as a great springboard to inform your data collection,” Mesaglio explains.

The platform’s impact extends well beyond environmental studies. Citizen science projects now span astronomy, archaeology, and health research. NASA’s Zooniverse platform enlists volunteers to classify galaxies, while marine conservation projects like NOAA’s Beach Watch gather data on ecosystems and invasive species.

Carrie Seltzer, iNaturalist’s head of engagement, emphasizes the growing importance of community participation: “The tenfold increase in peer-reviewed research using our data demonstrates that community science isn’t just a nice addition to traditional research methods; it’s becoming essential for understanding our rapidly changing planet.”

The international study involved researchers from 15 institutions across six countries, highlighting the global significance of this trend. As smartphones become more widespread and apps like iNaturalist grow in popularity, the line between professional scientists and curious citizens continues to blur – creating new opportunities for discovery that benefit everyone.