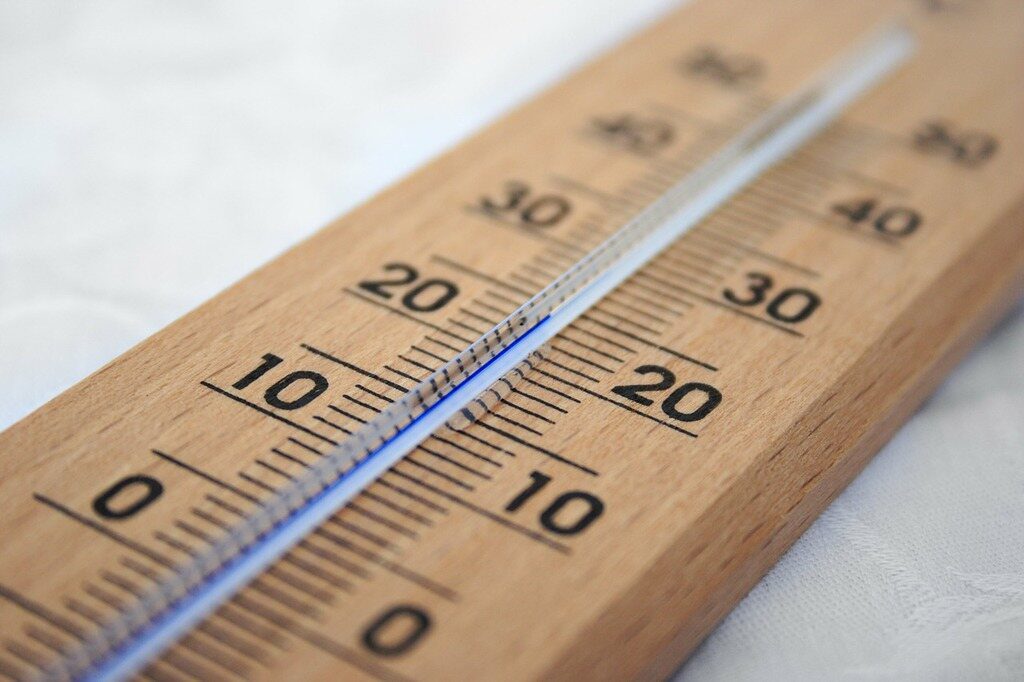

Extreme heat killed an estimated 110,000 Europeans in 2022 and 2023 combined, but a new forecasting system could help save lives by predicting heat-related deaths about a week ahead of time.

A team from Uppsala University tested their new forecasting model during Europe’s deadliest summers in recent memory. Unlike traditional warning systems that only track temperature, this system combines weather forecasts with health statistics to predict how many people might die.

“We tested it on Europe’s extremely hot summers in 2022 and 2023 and were able to make forecasts about a week in advance,” says Emma Holmberg, the study’s lead author. “Our forecasting system takes both meteorological data and health statistics into account, which enables us to more accurately predict how heat may affect deaths.”

The system works by creating district-level forecasts that account for regional differences. The research team calculated each area’s unique relationship between temperature and mortality, recognizing that people in different regions have different vulnerabilities to heat.

What surprised researchers was how well the model performed even in the hottest regions during record-breaking heat. During the 2022 heatwave on the Iberian Peninsula, their forecasts proved significantly more accurate than traditional methods that rely on historical averages.

More Posts

Climate scientists expect extreme heat events like those seen in 2022 and 2023 to become increasingly common. In southern Europe, where heat-related mortality rates are highest, accurate forecasting could save thousands of lives.

Elderly people and those with underlying health conditions face the greatest risk from extreme heat. When temperatures soar, the human body struggles to cool itself, leading to heat exhaustion, heatstroke, and in severe cases, death.

The new forecasting approach could transform how authorities issue heat warnings. By including expected mortality figures in public alerts, officials could direct resources where they’re most needed.

“By including heat-related mortality in heat warnings, authorities can focus resources where they are needed, especially on the elderly, sick or other vulnerable groups,” Holmberg explains.

Heat currently causes about 175,000 deaths annually across Europe, according to the World Health Organization. Europe is warming twice as fast as the global average, with the three warmest years on record occurring since 2020.

The Uppsala researchers published their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Their work represents an important step toward reducing the growing death toll from extreme heat in a warming world.

As climate change intensifies, tools that help communities prepare for deadly heatwaves will become increasingly vital. This new forecasting system offers a practical way to protect those most vulnerable to rising temperatures.