Snow leopards face an uncertain future due to their extremely low genetic diversity, according to a groundbreaking study published October 7, 2025, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The Stanford-led research reveals these elusive big cats have the lowest genetic diversity among the Panthera species, making them especially vulnerable to rapid environmental changes.

Scientists sequenced the genomes of 41 snow leopards — 35 from the wild and 6 from zoos — expanding dramatically from the mere four genomes previously available. This extensive work required collaboration across 11 countries to collect blood and tissue samples for analysis at Stanford University.

“Snow leopards live in these really untouched areas, unlike other big cat species, which have suffered from human impact already,” explains Katie Solari, the study’s first author and research scientist at Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences. “They don’t have many individuals. They don’t have much genetic diversity. Snow leopards are just not well situated to deal with changes that are likely coming their way.”

Unlike cheetahs and Florida panthers, whose low genetic diversity resulted from recent population crashes (known as bottlenecks), snow leopards appear to have maintained small but stable numbers throughout their evolutionary history. This crucial difference has implications for their survival prospects.

More Posts

The research team, led by Stanford biologist Dmitri Petrov, discovered that snow leopards have a significantly lower “homozygous load” — fewer instances of inheriting identical copies of harmful genetic mutations from both parents. This suggests that over time, harmful mutations were naturally eliminated from the population when animals carrying them failed to reproduce successfully.

This process of “purging” harmful genes explains why snow leopards have remained relatively healthy despite their small population of less than 8,000 animals scattered across the arid mountain regions of 12 Asian countries, including Russia, Afghanistan, Nepal, and China (Tibet Autonomous Region).

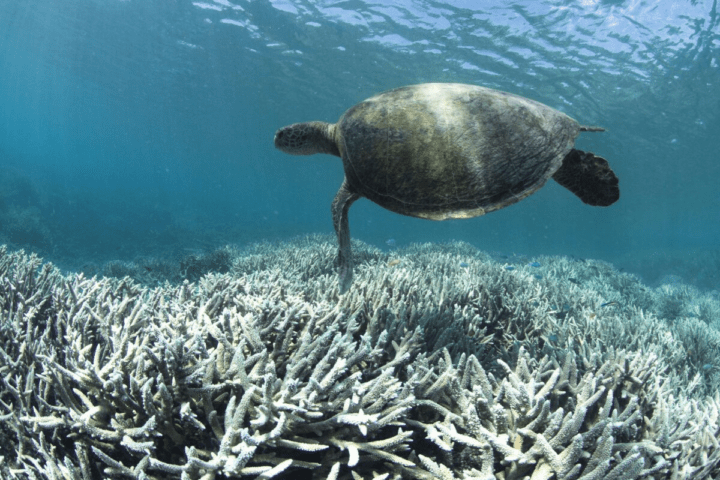

However, this historical resilience doesn’t guarantee future survival. “Because their habitat is so inhospitable, human population growth didn’t really affect snow leopards very much, but climate change will,” says Petrov. “Humans don’t need to show up in their mountains to build or start agriculture. The climate changes, and it affects everyone and everything, even in such remote areas.”

Snow leopards have evolved specialized adaptations to their extreme high-altitude habitat, with temperatures often dropping below freezing. As climate patterns shift, these adaptations may become less beneficial. Their limited genetic diversity further restricts their ability to adapt quickly to environmental changes, making them vulnerable.

The research highlights two main genetic groups among snow leopards — northern and southern populations separated around the Dzungarian Basin, with a secondary divide near the Taklamakan Desert. These distinctions may prove important for conservation planning.

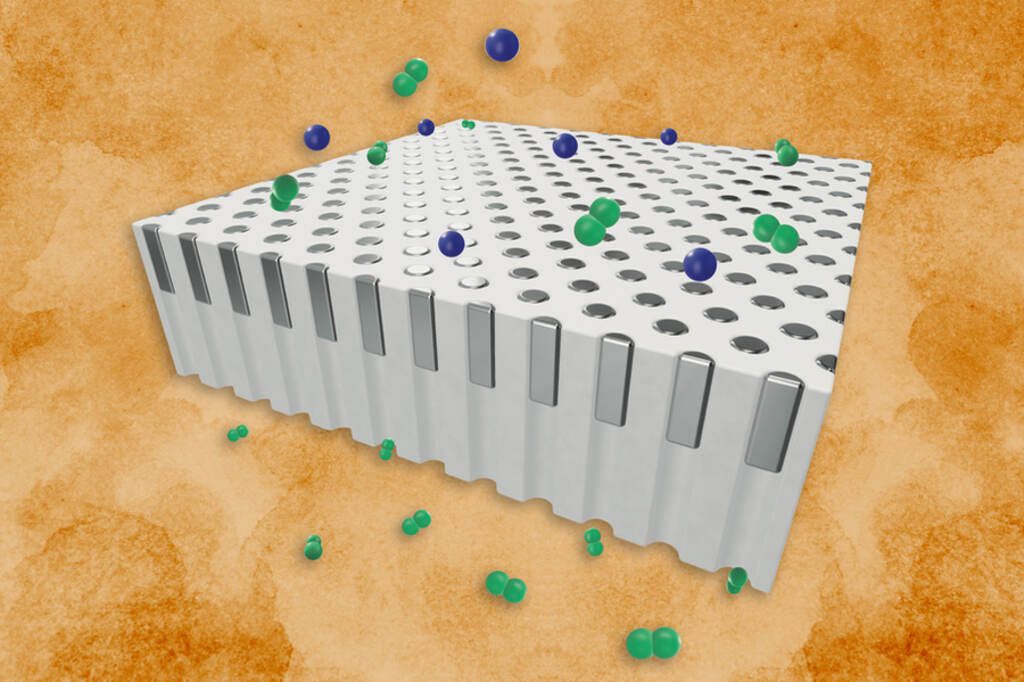

Scientists are currently working to develop genetic testing methods that can analyze snow leopard feces, allowing researchers to monitor wild populations without the need to trap or sedate these shy animals. The Program for Conservation Genomics at Stanford, founded by Petrov, is developing this technology.

As keystone predators, snow leopards primarily hunt mountain ungulates like blue sheep and Siberian ibex, as well as smaller mammals like pikas. Their disappearance would signal broader ecosystem decline.

“If their habitat starts degrading, then snow leopards might go extinct fairly easily, simply because there’s just not much ecological space for them and the total population is so small,” Petrov warns. The study’s insights will guide conservation efforts for this species, particularly as climate change threatens to reshape their remote mountain habitats faster than they can adapt.