Your tap water might contain perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances – chemicals that don’t break down naturally and can stay in your body for years. The EPA just made some big changes to how we’re dealing with these contaminants.

What Just Happened?

On May 14, 2025, the Environmental Protection Agency announced major changes to drinking water standards for PFAS – those persistent chemicals found in everything from non-stick pans to firefighting foam. The agency is keeping limits on two well-known PFAS but giving water companies more time to clean up their act.

EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin made it clear during a Senate hearing: “That is not accurate. That is not what the agency announced.” when asked if the agency was weakening standards. He added, “But that doesn’t mean that it gets weaker. The number might end up going lower, not higher.”

The Two-Track Approach: What Stays, What Goes

The agency is taking a split approach. They’re maintaining the strictest limits ever set for PFOA and PFOS – both set at 4 parts per trillion. That’s incredibly low – imagine a pinch of salt in 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools. But here’s the catch: water systems now have until 2031 instead of 2029 to meet these standards.

The bigger change? EPA is rescinding and reconsidering the limits for the other four listed in the initial regulation – PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA, and PFBS. This includes GenX chemicals – those replacements for older PFAS that communities in North Carolina know all too well.

Why These Changes Matter for Your Health

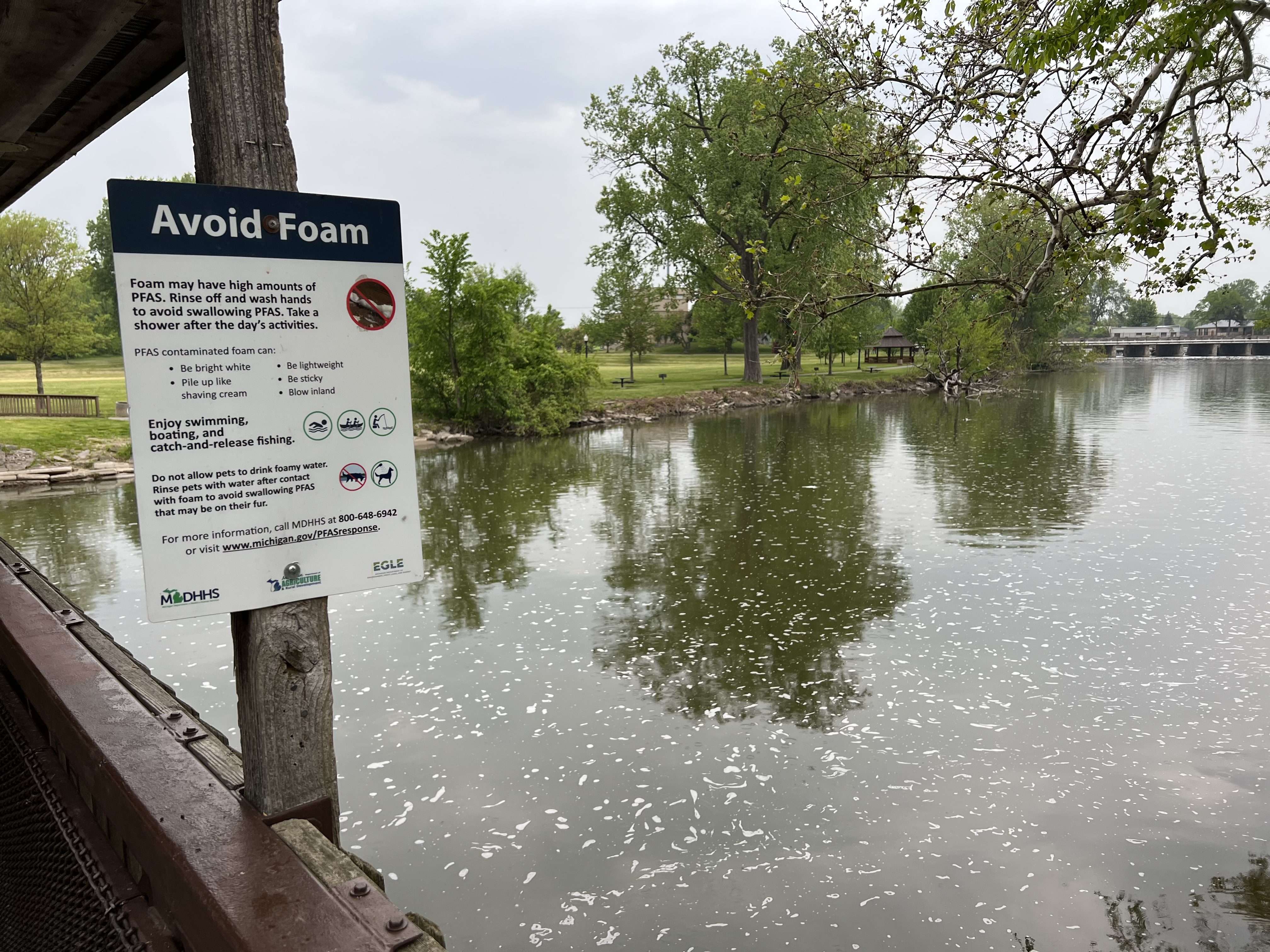

PFAS aren’t called “forever chemicals” for nothing. They’re sometimes called “forever chemicals” because they contain strong molecular bonds that persist for decades. Long-term exposure to PFAS has been linked with harms to human health, such as certain cancers or damage to the liver and immune systems.

The EPA estimates that 6-10% of water systems serve water with excess PFAS levels, according to the 2024 regulations, affecting some 100 million people in the U.S. Studies have connected PFAS exposure to kidney and testicular cancers, decreased fertility, liver damage, and developmental problems in children.

The PFAS OUT Initiative: Help for Struggling Water Systems

Recognizing that many water utilities – especially smaller, rural ones – are overwhelmed by the costs, the EPA launched something called PFAS OUT. “EPA will share resources, tools, funding, and technical assistance to help utilities meet the federal drinking water standards. PFAS OUT will ensure that no community is left behind as we work to protect public health and bring utilities into compliance with federal drinking water standards.”

National Rural Water Association CEO Matthew Holmes welcomed the changes: “EPA has done the right thing for rural and small communities by delaying implementation of the PFAS rule. This commonsense decision provides the additional time that water system managers need to identify affordable treatment technologies and make sure they are on a sustainable path to compliance.”

The Environmental Justice Reality

What’s particularly troubling is how PFAS contamination hits hardest where people can least afford it. Community water systems contaminated with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) serve greater proportions of Hispanic/Latino and non-Hispanic Black populations and contain greater numbers of PFAS sources within their watersheds.

Research shows that each additional industrial facility, military fire training area, and airport in a CWS watershed was associated with a 10–108% increase in perfluorooctanoic acid and a 20–34% increase in perfluorooctane sulfonic acid in drinking water. Rural communities face their own struggles – among rural water systems, each percentage-point greater proportion of residents under the federal poverty line was associated with 10% greater odds of detecting PFOA and any of the five PFAS.

The Price Tag and Who Pays

Installing PFAS removal systems isn’t cheap. According to EPA analysis, it would cost $1.5 billion a year for water companies to comply with the regulation. The technology exists – granular activated carbon, reverse osmosis, and ion exchange systems can remove PFAS – but the upfront costs are substantial.

Similar Posts

Cities like Wilmington, North Carolina, which faced severe GenX contamination from a nearby Chemours plant, have successfully implemented these systems. For example, the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority, serving Wilmington, NC – one of the communities most heavily impacted by PFAS contamination – has effectively deployed a granular activated carbon system to remove PFAS regulated by this rule.

Legal Challenges and the Anti-Backsliding Question

Environmental groups are already sharpening their legal knives. Erik Olson, the senior strategic director for health at the Natural Resources Defense Council, an advocacy group that is a party to the lawsuit, said the Safe Drinking Water Act’s “anti-backsliding” provision bars the agency from repealing or weakening the drinking water standard.

The law is designed to prevent the EPA from loosening standards once they’re set. “The law is very clear that the EPA can’t repeal or weaken the drinking water standard. Any effort to do so will clearly violate what Congress has required for decades,” Olson said.

Looking at the Bigger Picture

This isn’t happening in isolation. The Trump administration also withdrew a proposal that would have limited PFAS discharges from industrial sources, and delayed compliance dates for PFAS reporting requirements under toxic chemical laws. Administrator Zeldin, despite his current positions, was a founding member of the PFAS Congressional Taskforce and a strong supporter of the PFAS Action Act, legislation to provide funding to support local communities cleaning up PFAS-contaminated water systems.

Understanding the Science Behind the Rules

PFAS is not just one chemical but a class of thousands of synthetic compounds. The carbon-fluorine bond that makes them so useful in products also makes them incredibly stable – they don’t break down in nature or our bodies. When you’re exposed to PFAS through drinking water, food, or consumer products, they accumulate over time.

The Biden administration’s original rule was based on extensive research showing health effects at extremely low levels. The EPA in 2016, for example, said the combined amount of the two substances should not exceed 70 parts per trillion. The Biden administration later said no amount is safe.

What Comes Next

The EPA plans to finalize these changes through a formal rulemaking process, with a proposed rule expected this fall and final action by spring 2026. Meanwhile, water systems must continue monitoring for PFAS and reporting results to their customers.

The agency is also moving forward with efforts to control PFAS at the source through industrial discharge limits and is working on a liability framework to ensure that polluters – not water utilities and their customers – bear the costs of cleanup.

The Bottom Line

The EPA is walking a tightrope between public health protection and practical implementation challenges. While maintaining protections for the two most studied PFAS, the decision to pull back on limits for four others and extend compliance deadlines reflects the complex realities of water system management.

The benefits of reducing PFAS in drinking water would equal or exceed the costs, the agency said, in terms of less cancer and fewer heart attacks, strokes and birth complications in the affected population.

For millions of Americans, especially those in rural, tribal, and disadvantaged communities disproportionately affected by PFAS contamination, these regulatory decisions will determine whether their tap water becomes safer sooner or later. The challenge remains: how do we balance the urgent need for clean water with the practical realities of infrastructure upgrades and costs?

As Administrator Zeldin noted, “What we are going to have to be is extremely thoughtful in figuring this out.” The question is whether this thoughtfulness will translate into meaningful protection for all communities, regardless of their resources or political influence.