Most Air Cleaning Devices Lack Real-World Health Evidence

New research review of 672 studies reveals significant gaps between air cleaning technology marketing claims and scientific proof for human infection prevention

A comprehensive research review led by scientists at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) analyzed 672 research studies spanning from 1929 to 2024. The findings, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, present a critical picture: although air-cleaning technologies—including HEPA filters, ultraviolet light systems, ionizers, and advanced ventilation—are commonly installed in homes, schools, and workplaces to prevent respiratory infections, most have never been tested on humans to verify they actually reduce illness.

📊 Critical Research Findings

🔍 What Technologies Were Evaluated

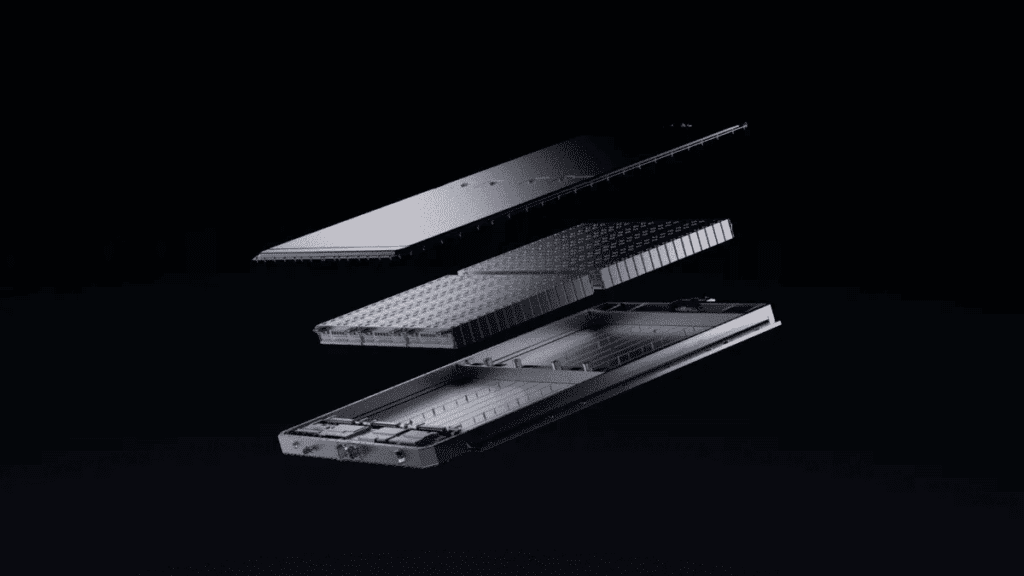

The research team examined four primary categories of engineering controls designed to clean indoor air and prevent respiratory virus transmission. HEPA filters (high-efficiency particulate air) work through mechanical filtration, trapping particles as small as 0.3 micrometers. UV light systems use ultraviolet radiation to inactivate viruses and bacteria. Ionizers and plasma-based devices generate charged particles or plasma to neutralize pathogens. Advanced ventilation systems increase outdoor air intake and improve air circulation within buildings.

The research identified that most studies measured surrogate outcomes—such as tracer gases, dust particle counts, or harmless test microbes—rather than tracking whether people actually got sick less often. This distinction matters significantly: a device may reduce particles in laboratory air without necessarily preventing infections in real human environments.

⚙️ Understanding the Technologies

📈 How Studies Measured Results

The research team categorized studies by their measurement approach. This breakdown reveals why the evidence gap matters so critically.

Why This Distinction Matters: Laboratory measurements of air cleanliness do not automatically translate to infection prevention in actual homes, schools, or workplaces. Real-world environments have variable ventilation patterns, occupancy levels, and user behaviors that laboratory chambers cannot replicate. People also shed respiratory viruses in ways that laboratory test microbes do not.

⚠️ Safety Gaps: The Byproducts Problem

Among the 112 studies examining pathogen-killing air-cleaning technologies, only 14 tested for harmful byproducts. This critical gap in safety research is particularly concerning because some widely-used devices produce ozone—a gas recognized by health agencies as a lung irritant that can worsen respiratory conditions.

Ozone can trigger respiratory distress, especially in children and people with chronic lung or heart disease. When ozone reacts with other indoor chemicals, it can also form additional harmful compounds such as formaldehyde and other secondary organic compounds.

✓ How to Evaluate an Air Cleaner: Practical Checklist

If you’re considering purchasing an air cleaning device, use this checklist based on research recommendations:

🔬 What Researchers Say Is Needed

The research team identified critical priorities for future work. First, studies must evaluate air-cleaning technologies in real-world environments—actual homes, schools, offices, and hospitals—rather than controlled laboratory chambers. Second, researchers need to track whether people experience fewer infections or illness, not just whether devices reduce particles in the air. Third, safety assessment must become standard: testing for harmful byproducts like ozone, formaldehyde, and other reactive chemicals should occur before devices enter the consumer market.

Fourth, funding for air-quality research should be independent of the manufacturers producing the technologies being tested. As the lead researchers noted, some existing studies received funding from device manufacturers, creating potential conflicts of interest. Finally, scientists recommend developing standardized health-related outcome measures so that future research results can be reliably compared and used to guide public health policy.

💡 Evidence-Based Recommendations

📚 Additional Resources

Explore related articles on indoor air quality, respiratory health, and disease prevention:

Summary

The research published in the Annals of Internal Medicine documented the evidence gap surrounding air-cleaning technologies marketed to prevent respiratory infections. Of 672 studies analyzed spanning nearly a century, 57 (≈8.5%) included human participants to test actual illness reduction. Most research occurred in laboratory chambers and relied on surrogate measurements of effectiveness rather than tracking real infection rates in people.

Safety concerns emerged regarding certain technologies, particularly ionizers, plasma-based systems, and some ultraviolet light devices that produce ozone and other potentially harmful byproducts. Only 14 of 112 studies on pathogen-killing technologies evaluated long-term safety, particularly for vulnerable populations such as children and people with chronic respiratory or cardiovascular illnesses.

The findings emphasize that established practices—opening windows, regular surface cleaning, and maintaining adequate ventilation—remain effective approaches to improving indoor air quality. The research underscores the importance of independent testing, transparent information about device safety and maintenance, and questioning marketing claims that lack human-health outcome evidence.