The Trump administration has proposed removing or revising Endangered Species Act protections for 11 animals that closely resemble threatened or endangered species. This change could affect pumas, butterflies, sturgeon, and turtles that share physical similarities with their endangered counterparts.

The proposal targets species protected under the “look-alike” provision of the Endangered Species Act. This rule protects animals that appear similar to endangered species to prevent accidental harm through misidentification. Wildlife officials often struggle to tell these similar-looking animals apart in the field.

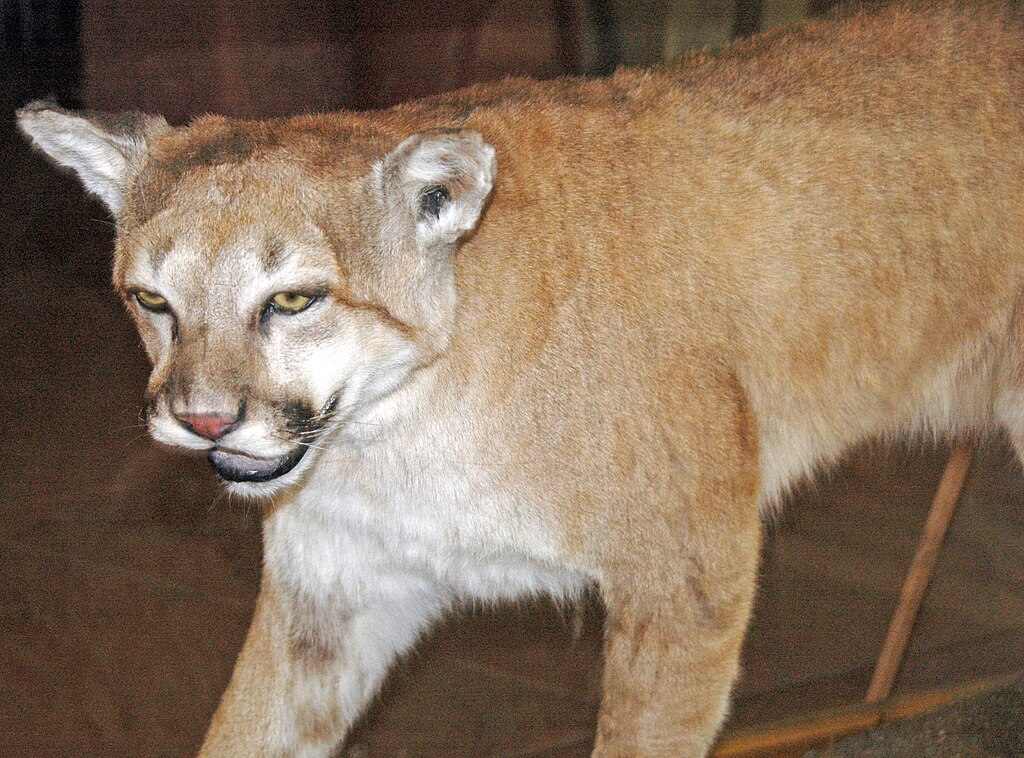

Among the species losing protections are pumas, which resemble the endangered Florida panther; three butterfly species (cassius blue, ceraunus blue, and nickerbean blue) that look like the endangered Miami blue butterfly; and shovelnose sturgeon, which are easily confused with endangered pallid sturgeon. The plan also revises protections for bog turtles, desert tortoises, and Pearl River map turtles.

“It’s disturbing to see the Trump administration moving to strip crucial Endangered Species Act protections from yet more animals, with potentially devastating consequences,” said Lia Comerford, a senior attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity. “These protections are still sorely needed to protect the imperiled species from further decline.”

This proposal comes alongside another significant change to the Endangered Species Act. In April 2025, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service proposed redefining “harm” under the Act to exclude habitat modification. Currently, the law treats damage to an animal’s habitat as harmful to the species. The new definition would allow activities that destroy habitat as long as they don’t directly target protected animals.

Similar Posts

The proposed changes have drawn criticism from environmental groups and lawmakers. Three Democratic senators—Adam Schiff, Sheldon Whitehouse, and Cory Booker—sent a letter on May 5, 2025, asking the administration to explain its analysis and plans to protect affected species.

Conservation groups argue these changes will weaken enforcement efforts. When similar-looking species are protected together, wildlife officers can more easily prevent illegal hunting, collection, or harm. Without these protections, officers would need to make difficult on-the-spot identifications between nearly identical species.

The timing is concerning to environmental advocates. According to statistics cited by conservation groups, 21 species were removed from the endangered list in 2023 because they went extinct. Studies show that habitat destruction affects 88% of threatened species worldwide.

For species like the Florida panther in South Florida and the Miami blue butterfly, limited to small areas of coastal South Florida, any reduction in protection could pose serious threats.

The public has until May 19, 2025, to comment on the “harm” definition change, though the deadline for comments on the look-alike protection removal hasn’t been clearly specified.

Environmental groups, including the Center for Biological Diversity and Earthjustice, have signaled they may challenge these changes in court if finalized. A 1995 Supreme Court ruling previously upheld the inclusion of habitat modification in the definition of “harm” under the Endangered Species Act.

“Nothing has changed for these pumas, blue butterflies, sturgeon and turtles,” noted Comerford. “They still look like they did yesterday and will continue to be easily mistaken for imperiled species.”