Wild African elephants communicate using individual vocal labels embedded within their infrasonic rumbles, according to research published in Nature Ecology and Evolution in June 2024. Scientists analyzed 469 rumbling calls from 101 elephants across Kenya’s Samburu National Reserve, Buffalo Springs National Reserve, and Amboseli National Park using machine learning algorithms that correctly identified intended recipients 27.5% of the time.

The discovery places African elephants among only three animal groups known to use name-like calls, joining bottlenose dolphins and certain parrots. However, elephants differ from these species by using arbitrary vocal labels rather than imitating the sounds made by the animals they address.

“Dolphins and parrots call one another by ‘name’ by imitating the signature call of the addressee,” said lead author Michael Pardo, who conducted the study as an NSF postdoctoral researcher at Colorado State University and Save the Elephants. “By contrast, our data suggest that elephants do not rely on imitation of the receiver’s calls to address one another, which is more similar to the way in which human names work.”

Elephants produce infrasonic calls in the 14-35 Hz frequency range, well below human hearing capacity. These rumbles can travel up to 10 kilometers across savanna landscapes at intensities approaching 120 decibels. The calls enable coordination across vast distances where visual contact becomes impossible.

Co-author George Wittemyer from Colorado State University observed behavioral patterns that suggested individual addressing: “Elephants do these really interesting behaviours where sometimes when they’re in a big group of females or a mate check of a group will give a call. The entire group will respond, they’ll group up around her or they’ll follow her. Then at other times, she gives seemingly a very similar call and nobody will respond, nobody will react, except for a single elephant. So that indicates that they have a means by which to communicate to who they want to talk to.”

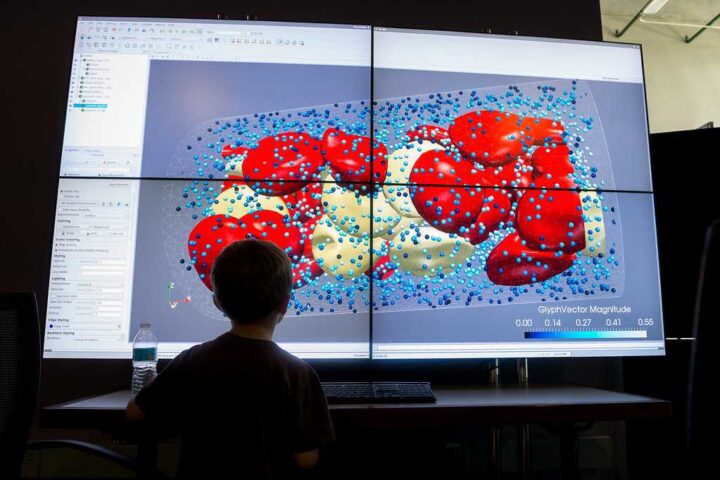

The research team used sophisticated acoustic analysis to extract features from recorded calls, including mel-frequency cepstral coefficients, spectral centroids, fundamental frequency contours, and harmonics. When researchers fed meaningless control data to their machine learning model, classification accuracy dropped to just 8%, confirming genuine acoustic patterns encode recipient identity.

Behavioral validation came through playback experiments with 17 wild elephants. Animals responded more energetically to recordings originally addressed to them, approaching speakers 128 seconds faster and producing 2.3 times more vocalizations compared to hearing calls meant for other family members. Sometimes elephants entirely ignored vocalizations addressed to others.

“Just like humans, elephants use names, but probably don’t use names in the majority of utterances, so we wouldn’t expect 100%,” explained study author Mickey Pardo, now at Cornell University.

Elephant vocal anatomy enables this complex communication system through a larynx structure about 7.5 centimeters long. A typical male rumble vibrates around 12 Hz, more than three octaves below a man’s voice, while females rumble around 13 Hz and calves around 22 Hz. The fundamental frequency within a single elephant call may vary over four octaves.

Joyce Poole, scientific director of ElephantVoices and study co-author, had suspected this phenomenon for decades: “I suspected elephants had a way of directing their calls to specific individuals, but had no idea how one would tease this out.”

Kurt Fristrup, the Colorado State University researcher who developed signal processing techniques for the study, noted the discovery’s implications to Karmactive: “Our finding that elephants are not simply mimicking the sound associated with the individual they are calling was the most intriguing. The capacity to utilize arbitrary sonic labels for other individuals suggests that other kinds of labels or descriptors may exist in elephant calls,” Fristrup informed Karmactive.

Atmospheric conditions significantly affect infrasonic transmission. Temperature inversions during evening hours create acoustic ducting effects that expand an elephant’s communication area from 50 square kilometers at midday to 300 square kilometers in the evening. Savannah elephants make most of their loud low-frequency calls during hours of optimal sound propagation.

The research spanned multiple locations and decades of recordings. Scientists analyzed calls from recent fieldwork between 2019-2022 plus archival recordings from Amboseli National Park dating to the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. Researchers focused on contact, greeting, and caregiving rumbles as these call types most likely contained individual addressing components.

“If all we could do was make noises that sounded like what we were talking about, it would vastly limit our ability to communicate,” said co-author George Wittemyer, a professor in CSU’s Warner College of Natural Resources and chairman of the scientific board of Save the Elephants.

The naming system facilitates herd management across elephant societies. Contact calls help maintain cohesion when family members are separated by up to 2 kilometers. Greeting rumbles facilitate reunions between adult females after separation. Caregiving calls enable mothers to address specific calves within multi-generational herds.

Pardo explained to Karmactive that understanding elephant communication could help predict their movements: “If we were to find that elephants talk to each other about where they are planning to go, we might be able to predict their movements by eavesdropping on their communication, and create better early warning systems for people to avoid accidental run-ins with elephants.”

The research also has broader ecological implications. As Pardo told Karmactive, elephants function as ecosystem engineers whose social behavior affects movement patterns and feeding habits, which in turn impact other species sharing their habitat.

“Elephants are incredibly social, always talking and touching each other — this naming is probably one of the things that underpins their ability to communicate to individuals,” explained Wittemyer.

Several questions remain unanswered. Scientists cannot yet isolate the specific acoustic segments that constitute elephant names within longer rumbles. “I’d really like to be able to isolate the name of specific individual elephants because if we could do that, we could answer a lot of other questions that we weren’t able to fully figure out in this study,” Pardo explained.

Research findings suggest different elephants might use personalized variations when addressing the same individual. “Just as the human nicknames Liz, Elizabeth, and Ellie have certain features in common despite being distinct words, it may be that different elephants address the same individual with somewhat similar yet distinct labels,” Pardo noted.

Similar Posts

Human-elephant conflict escalates globally as agricultural expansion fragments elephant corridors. In Sri Lanka’s elephant range regions, between 200 and 400 elephants are killed annually, and more than 1,200 people have died from elephant encounters within a decade. Similar patterns occur across Africa and Asia.

Fristrup emphasized to Karmactive that understanding elephant perception and interaction is foundational for addressing these conflicts: “How elephants perceive and interact with each other, and their environment, is foundational knowledge for understanding human-elephant conflicts, for designing and managing reserves, and predicting the consequences of culling, translocations, and reintroductions.”

Early warning systems using acoustic monitoring show promise for conflict mitigation. In Karnataka’s Hassan district, forest official A K Singh reported that early warning systems have “reduced the injuries and even deaths almost to zero in just a year since its initiation. About 35,000 people are getting warnings about elephant presence and then they become alert.”

The study methodology required extensive ethical protocols. Researchers maintained 50-100 meter buffers from elephant herds to minimize behavioral disturbance. Playback experiments limited individual elephants to two trials per week, each at ~90 dB, conducted between 07:00-10:00 hrs, to minimize stress.

Pardo emphasized to Karmactive the ethical importance of studying cognition in wild settings rather than captivity: “Capturing wild animals and forcing them to live in captivity, even temporarily, usually causes them to suffer.” The wild approach also provides more ecologically relevant insights into how elephants use their abilities naturally.

Fristrup informed Karmactive that researchers must consider how their presence affects elephant behavior: “They are undoubtedly observing us as we observe them, so study designs should contemplate how the researchers’ behavior and methods might alter the phenomena we seek to study.” Habituation protocols required weeks of gradual vehicle introduction before elephants ignored researchers sufficiently for natural behavior observation.

Both African elephant species face population declines from poaching and habitat loss. Forest elephants received critically endangered status in 2021 while savanna elephants were listed as endangered, whereas previously both species were treated as a single vulnerable species.

The research carries important conservation implications beyond scientific knowledge. Pardo told Karmactive that understanding elephant intelligence could inspire greater public support: “By giving people a better appreciation for the cognitive abilities of elephants and how similar they are to humans in many ways, we may help inspire people to care more about elephants.” This could improve fundraising for conservation and discourage ivory purchasing.

The findings also raise ethical questions about elephant management. As Pardo explained to Karmactive, recognizing elephants as cognitively sophisticated individuals should influence conservation decisions: “If we only consider elephants as data points in a population, then lethal management strategies may seem reasonable. But when we recognize that they are sentient and highly intelligent individuals, that changes the moral calculus and calls for alternative approaches.”

“While conversing with pachyderms remains a distant dream, being able to communicate with them could be a gamechanger for their protection,” suggested Wittemyer regarding potential future applications.

The research represents collaboration between Colorado State University, Save the Elephants, ElephantVoices, and the Amboseli Elephant Research Project. Authors include Michael A. Pardo, Kurt Fristrup, David S. Lolchuragi, Joyce H. Poole, Petter Granli, Cynthia Moss, Iain Douglas-Hamilton, and George Wittemyer.

Statistical validation employed k-fold cross-validation and permutation tests confirming machine learning results exceeded random chance performance. Behavioral validation through playback experiments provided independent verification that elephants actually perceive and respond to acoustic features identified by computational algorithms.

The research team analyzed 469 rumbles directed by 101 known callers to 117 known receivers using supervised machine-learning classification. The model predicted intended recipients 27.5% of the time, well above random chance. Playback trials with 17 elephants verified that individuals approached and vocalized more readily when hearing calls addressed to themselves compared to calls meant for other family members. Analysis confirmed elephants use arbitrary vocal labels rather than imitating recipients’ rumbles, distinguishing them from dolphins and parrots. These results built on decades of elephant cognition research, including vocal learning studies and long-term field observations in Amboseli.

The Nature Ecology & Evolution study documented that wild African elephants use individually specific name-like calls, verified through machine-learning classification and playback experiments. Elephants’ use of arbitrary vocal labels aligns with findings on vocal learning and social cognition while displaying unique complexity. This research complements previous work on mirror-self recognition and vocal learning in elephants.