A decade-long study from the University of Vermont reveals that simple wildlife underpasses have slashed amphibian deaths by over 80% on a busy Vermont road, offering hope for these declining species.

Every spring, as temperatures rise and rain falls, thousands of frogs, salamanders and toads emerge from their forest homes and begin a dangerous journey. These small creatures travel from upland forests to wetlands to breed, often crossing roads that cut directly through their migration paths. Until recently, this journey meant death for many of them.

In Monkton, Vermont, the situation was particularly grim. Local residents counted over 1,000 dead amphibians on a single road during just two nights of migration in 2006. The scene was described by long-time resident Steve Parren as “real carnage” that was “disturbing” to witness.

“So many were being killed on the road,” said Parren, a retired state biologist who began tracking the problem in the 1990s after being tipped off about the mass deaths. “It was like having a second job, and then every rainy night I’d have to run out here and count salamanders and frogs.”

The problem isn’t unique to Vermont. Worldwide, amphibians face multiple threats including habitat loss, climate change, and deadly fungal diseases. Road mortality adds another significant pressure on these already vulnerable populations.

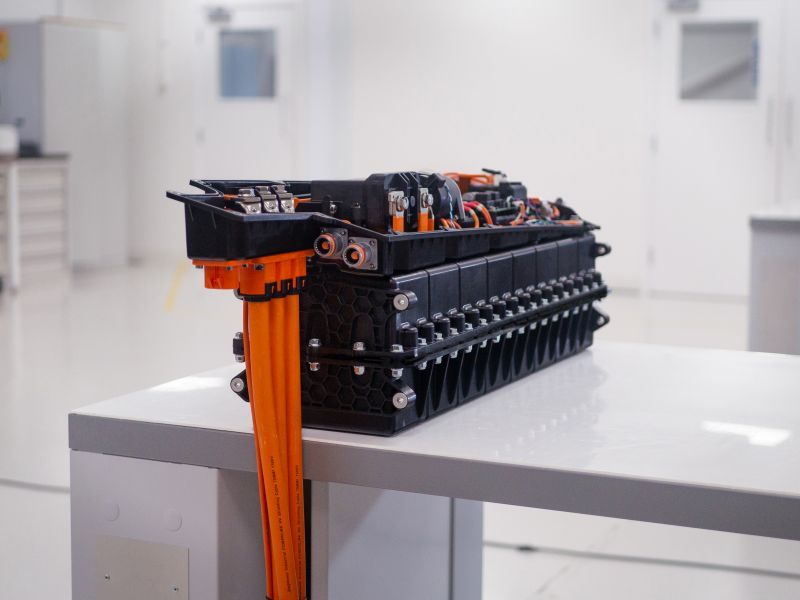

In 2015, after years of community concern and scientific monitoring, a solution emerged. The town of Monkton and the Lewis Creek Association installed Vermont’s first amphibian crossing tunnels beneath Monkton Road. These concrete underpasses, approximately four feet wide, were designed to allow amphibians to travel safely beneath the asphalt.

The results have been remarkable. The University of Vermont study, published in the Journal for Nature Conservation, documented an 80.2% overall reduction in amphibian road deaths. For ground-dwelling species like salamanders and toads that can’t climb, the mortality rate dropped by an astounding 94%.

“I didn’t realize how impactful they were going to be,” said Matthew Marcelino, the lead author of the study and an ecologist at UVM. “Going from thousands of amphibians to potentially dozens of amphibians killed in one night is really, really significant.”

The success hinges on thoughtful design. The tunnels include “wing walls” that extend from the sides, guiding the migrating amphibians away from the road surface and toward the safety of the tunnels. These walls prevent the small creatures from wandering onto the deadly pavement above.

Researchers used a rigorous “before-after-control-impact” approach, monitoring three zones: areas with underpasses and wing walls, buffer zones at the ends of the wing walls, and control areas far from any infrastructure changes. They collected data for five years before construction (2011-2015) and seven years after (2016-2022).

During rainy spring evenings when amphibians migrate, citizen scientists and researchers walked the roads, counting every amphibian—both living and dead. Their surveys documented 5,273 amphibians across twelve different species.

The findings included 1,702 spotted salamanders, nearly half of which were found dead before the underpasses were built. They also counted 2,545 spring peeper frogs, with almost 70% dead on the road prior to the intervention.

After the underpasses were installed, wildlife cameras captured 2,208 amphibians using just one of the tunnels during the spring of 2016. Interestingly, other wildlife also benefited—bears, bobcats, porcupines, raccoons, snakes, and birds were all filmed using the safe passages.

The underpasses offer a cost-effective solution. The Monkton project cost $342,397—significantly less than large mammal crossings that can range from $500,000 to nearly $100 million.

Similar Post

Professor Brittany Mosher, senior author of the study, explained why roads create such a deadly barrier: “Planners—state and federal transportation planners—often build roads between these steeper forested upland habitats and nice flat aquatic habitats. So the roads are placed exactly in the wrong spot if you were an amphibian planner.”

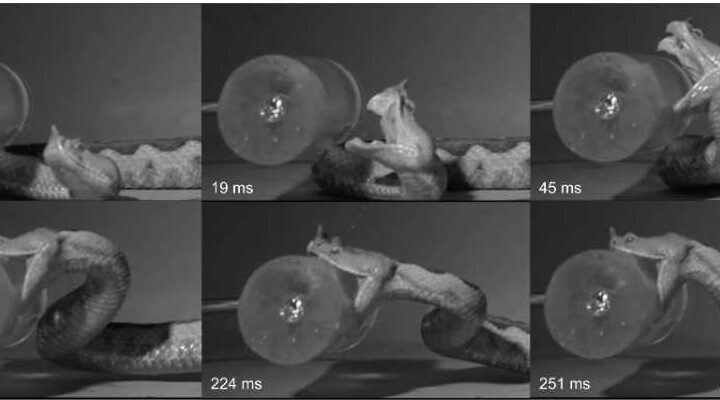

The timing of amphibian migration makes them especially vulnerable. “It’s usually sometime between late March and late April,” Mosher said. “Many species will breed in the same ponds. So it’s not just a single species migrating—it’s many, many species. And oftentimes, we see hundreds or thousands making this movement all at the same time.”

Unlike larger animals that can quickly cross roads, amphibians move slowly. A single frog or salamander might take several minutes to cross a road, putting it at high risk of being hit by vehicles.

The study provides the first long-term, peer-reviewed evidence that amphibian-specific wildlife underpasses in the northeastern U.S. effectively reduce road mortality. This success story began with community action, highlighting how local concern can drive meaningful conservation.

“This story began with local community members who were engaged and concerned,” Mosher noted. “And it provides a view for how other communities can protect their amphibian populations too.”

For Parren, who spent decades counting dead amphibians on rainy nights, the results bring a sense of accomplishment. “It makes me feel good, and it makes me feel hopeful that we can incorporate these sorts of projects going forward,” he said.

The Monkton wildlife crossing has gained international attention, demonstrating that infrastructure and nature protection can successfully coexist. Marcelino summed it up: “We really can build roads that work for both wildlife and people.”