When wildfires tear through forests, their destruction doesn’t end when the flames go out. A groundbreaking study reveals these fires leave a toxic legacy in waterways that can last nearly a decade, posing serious challenges for drinking water supplies and ecosystems.

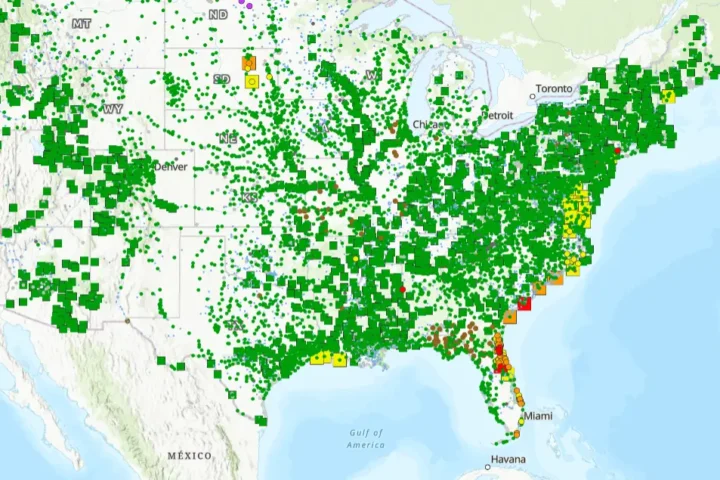

Scientists from the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) at the University of Colorado Boulder found that contaminants from wildfires can degrade water quality for up to eight years after a fire. This first-ever large-scale assessment, published in June 2025 in Nature Communications Earth & Environment, analyzed over 100,000 water samples from more than 500 watersheds across the Western United States.

“We were attempting to look at notable trends in post-wildfire water quality across the entire U.S. West, to help inform water management strategies,” said Carli Brucker, the study’s lead author.

The research team discovered that organic carbon, phosphorus, and turbidity (cloudiness) spike dramatically in the first one to five years after a fire. Even more concerning, nitrogen and sediment levels remain significantly elevated for up to eight years.

These impacts hit water supplies hard. Cities like Fort Collins and Greeley in Colorado have been forced to close drinking water intakes after wildfires contaminated the Poudre River. Denver Water spent over $10 million removing sediment from reservoirs following the 2002 Hayman Fire. A single large wildfire can increase water treatment costs by $10-100 million.

The contamination process begins when wildfires strip away protective vegetation and alter soil properties. When rain falls on burned areas, it washes massive amounts of ash, debris, and pollutants into nearby streams and rivers. Intense heat can even create water-repellent soil layers that prevent water from soaking in, increasing runoff and flash flood risks.

“Sometimes it can be a delayed effect,” explained Ben Livneh, CIRES Fellow and study co-author. “It’s not all happening right away, or sometimes you need a big enough storm that will mobilize enough of the leftover contaminants.”

Similar Posts

The impact varies widely between watersheds. “Some streams are completely clear of sediment after wildfires, and some have 2000 times the amount of sediment,” noted Brucker. This variability depends on factors like a fire’s proximity to rivers, soil types, vegetation, and local weather patterns.

For drinking water providers, these contaminants create serious treatment challenges. Dissolved organic carbon can react with chlorine used in water treatment to form harmful disinfection byproducts. High sediment loads can damage treatment equipment and increase costs substantially.

Aquatic ecosystems suffer too. Sediment smothers habitats and can physically harm fish gills. Nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus can trigger excessive algal growth that depletes oxygen in the water, potentially killing fish and other aquatic life.

With wildfires increasing in frequency and intensity due to climate change, communities face growing water security challenges. The research provides crucial data for developing more effective strategies.

“You can’t fund resilience improvements on general concerns alone,” Brucker said. “Water managers need real numbers for planning, and that’s what we’re providing.”

Some promising approaches include proactive forest management through prescribed burning and thinning to reduce fire intensity, and post-fire mitigation techniques like erosion control using biodegradable netting, contour log terraces, and mulch applications to stabilize burned slopes.

For the millions of people living in fire-prone regions, this research underscores a critical message: the impacts of wildfires on water resources extend far longer than previously understood, requiring long-term planning and investment to protect this essential resource.