When your skin itches from a rash or allergic reaction, scratching provides instant relief. Your skin feels better for a moment, then worse than before. Now, University of Pittsburgh researchers have discovered why this happens—and found a surprising benefit to scratching that no one expected.

The research team, led by Dr. Daniel Kaplan, tested their ideas using mice with skin reactions similar to common rashes. Some mice could scratch freely, while others wore tiny protective collars—think of the “cone of shame” that pets wear after surgery.

The results showed a clear pattern. Mice that scratched developed more swelling and inflammation. The scientists traced this to a specific chain of events: scratching triggers pain-sensing neurons to release “substance P,” activating immune cells called mast cells. These mast cells bring in other immune cells called neutrophils, causing the area to become red and swollen.

“In contact dermatitis, mast cells are directly activated by allergens, causing mild inflammation and itching,” explains Dr. Kaplan. “When you scratch, you’re triggering a second wave of mast cell activation—that’s why the rash gets worse instead of better.”

Similar Posts

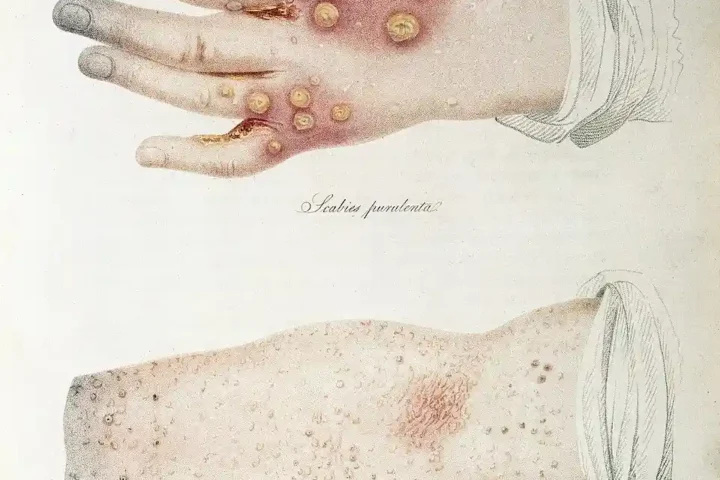

But here’s the unexpected twist: scratching also reduced levels of Staphylococcus aureus, the bacteria responsible for most skin infections. This discovery helps explain why scratching evolved as a natural response, despite its drawbacks.

The finding matters for anyone with skin conditions like eczema, poison ivy reactions, or contact dermatitis. That urge to scratch isn’t just a reflex—research shows it has connections to both immune response and infection control, even though the scratch itself can damage your skin.

Dr. Kaplan’s verdict is clear: “The damage that scratching does to the skin probably outweighs this benefit when itching is chronic.” His team is investigating new therapies for dermatitis and other inflammatory skin conditions that suppress inflammation by targeting receptors on mast cells.

The work, supported by National Institutes of Health funding, opens new possibilities for treating inflammatory skin conditions. Understanding the biological mechanisms behind scratching and inflammation helps advance research toward potential new treatments.

For now, when an itch occurs, remember: that momentary relief comes with consequences. While scratching shows some defensive benefits against bacteria, research suggests avoiding it, particularly for chronic skin conditions.