Wildlife officials have confirmed the first-ever detection of the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome in bats in Oregon. The fungus, with the scientific name Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd), was found in bat droppings at a bus shelter within Lewis and Clark National Historical Park in Clatsop County.

The sample likely came from a Yuma myotis bat. While the fungus has been detected, officials note that no bats in Oregon have yet shown signs of the actual disease.

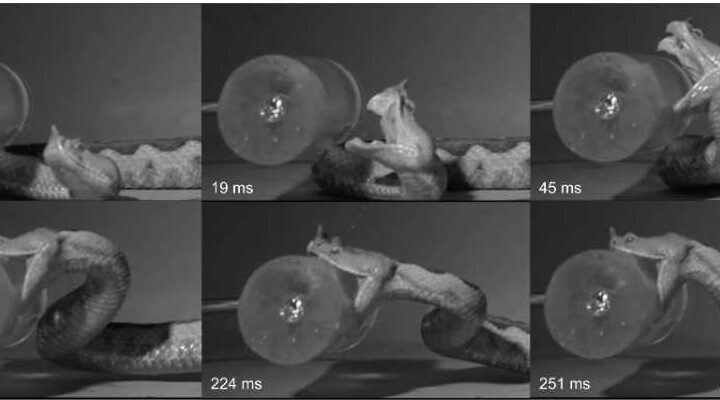

White-nose syndrome has killed millions of North American bats since it was first discovered in New York in 2007. The disease gets its name from the white fungus that grows on infected bats’ muzzles, ears, and wings during hibernation. This fungal growth irritates the skin and causes bats to wake up more often during winter, using up their stored fat reserves faster than normal. This leads to dehydration, starvation, and eventually death.

The fungus spreads mainly through direct contact between bats during hibernation. Though it doesn’t make humans sick, people can accidentally spread fungal spores on clothing and gear after visiting caves or other bat habitats.

Three bat species – northern long-eared, little brown, and tri-colored bats – have seen population declines of over 90% in parts of eastern North America due to white-nose syndrome. The disease has devastated bat populations since it was first documented in New York in 2007.

These bats play a critical role in agriculture too. In the United States alone, bats save farmers at least $3.7 billion per year in pest control services by eating insects that damage crops. A study found that in counties affected by white-nose syndrome, land rental rates fell by $2.84 per acre, and agricultural land decreased by 1,102 acres.

Similar Posts

Oregon’s multi-agency monitoring team has been actively looking for this fungus since 2011. The team includes state wildlife officials, federal agencies, and wildlife rehabilitators who check places where bats hibernate, raise young, and roost throughout the year.

Federal scientists and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife will increase surveillance around the positive detection area this winter. The testing labs at Oregon State University and the USGS National Wildlife Health Center will analyze samples to track the fungus’s spread.

The White-nose Syndrome Response Team, led by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, coordinates national efforts to study the disease and develop treatments. Scientists are working on several promising approaches to manage white-nose syndrome.

Oregonians can help by following these simple steps:

- Clean gear thoroughly after visiting caves or bat habitats

- Remove dirt first, then use isopropyl alcohol (50-70%) or hydrogen peroxide wipes

- Never touch bats, even if they appear sick

- Report unusual bat activity to ODFW’s Health Lab

This detection is concerning but not unexpected, as the fungus has already spread to Washington. The discovery highlights the importance of continued monitoring and research to protect these important insect-eaters that play a crucial role in Oregon’s ecosystems and agriculture.