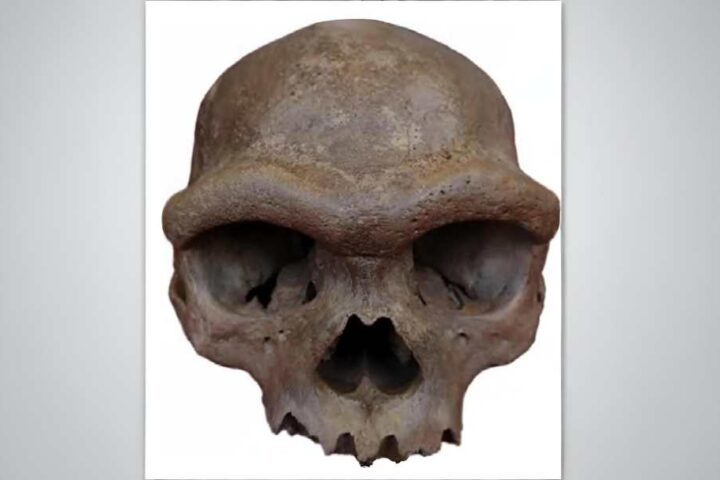

Scientists have made a groundbreaking discovery by extracting proteins from 2.2-million-year-old teeth found in South Africa’s Swartkrans cave. For the first time ever, researchers have determined the biological sex of ancient human relatives called Paranthropus robustus using molecular methods rather than just looking at bone size.

The breakthrough comes from a technique called paleoproteomics, which analyzes preserved proteins in ancient tissues, particularly dental enamel. Unlike DNA, which rarely survives beyond 20,000 years in hot regions like Africa, proteins can remain intact for millions of years.

“To extract ancient amino acids from hominin enamel this old and from this region of southern Africa is astonishing,” said Dr. Marc Dickinson, a chemist at the University of York and co-author of the study. “It opens entirely new avenues for understanding our evolutionary history on the continent.”

By examining specific proteins in the dental enamel of four fossilized teeth, researchers identified two males and two females. The team focused on a protein called amelogenin, which comes in different forms depending on biological sex.

One surprising finding challenged long-held assumptions. A specimen with smaller teeth (known as SK 835) that scientists had previously classified as female based on size was actually male according to the protein analysis.

Similar Posts

“Paleoanthropologists have long known that our use of tooth size to estimate sex was fraught with uncertainty, but it was the best we had,” said Paul Constantino, a paleoanthropologist not involved in the research. “Being able to accurately identify the sex of fossils using proteins will be hugely impactful.”

The analysis also revealed unexpected genetic diversity among these ancient human relatives. One individual showed distinct protein variations, suggesting it might have been less closely related to the others. This finding supports recent debates about whether Paranthropus encompasses multiple distinct species rather than just one.

Paranthropus robustus lived in southern Africa between 1.8 and 2.2 million years ago, coexisting with early Homo species like Homo habilis and Homo erectus. Though they walked upright, they had massive jaws for powerful chewing and were adapted for climbing trees.

The research team included scientists from the University of York, University of Copenhagen, and University of Cape Town’s Human Evolution Research Institute. Dr. Palesa Madupe, a co-lead author, emphasized the importance of this research being carried out through “meaningful and impactful collaboration with local stakeholders where the fossils are discovered.”

Looking ahead, researchers hope to eventually map the entire human family tree using these methods and develop less destructive techniques to analyze precious fossil samples.

The study was published in the journal Science.