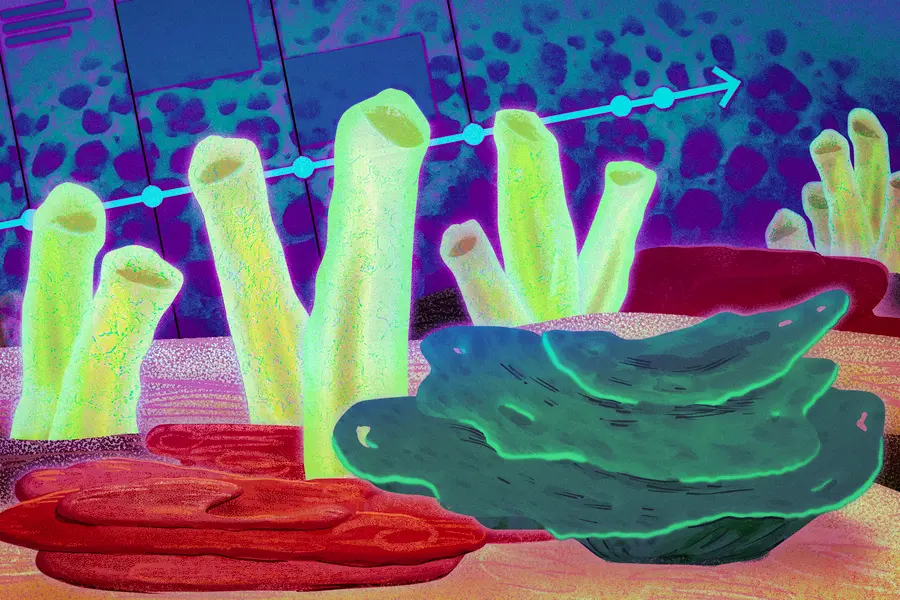

Scientists at MIT have uncovered compelling evidence that the humble sea sponge may have been Earth’s first animal. In a groundbreaking study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on September 29, 2025, researchers identified unique “chemical fossils” in rocks more than 541 million years old that point to ancient sponges.

The team found special compounds called steranes – geologically stable forms of sterols like cholesterol – preserved in ancient rock samples. These rare 30-carbon (C30) and even rarer 31-carbon (C31) steranes match those found in modern demosponges, a major class of sea sponges.

“These special steranes were there all along,” says lead researcher Lubna Shawar, formerly of MIT and now at Caltech. “It took asking the right questions to seek them out and to really understand their meaning.”

The discovery pushes back the timeline for when animals first appeared on Earth. The rock samples date to the Ediacaran Period (635-541 million years ago), well before the Cambrian explosion when most major animal groups suddenly appeared in the fossil record.

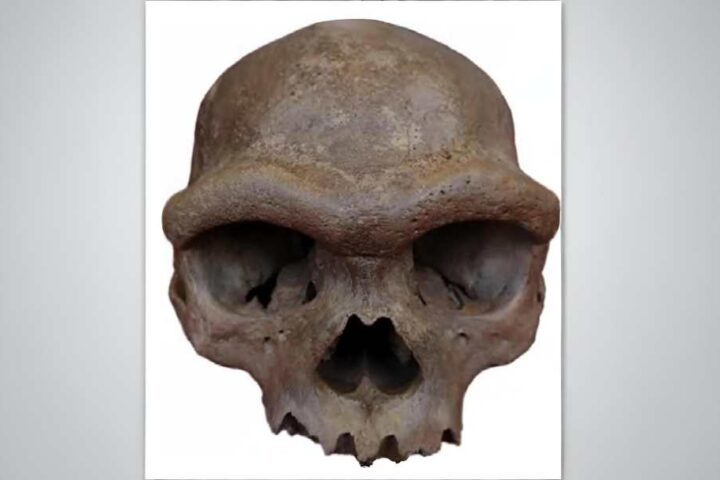

Roger Summons, Schlumberger Professor of Geobiology Emeritus at MIT, explains that these ancient sponges would have been quite different from many modern varieties. “We don’t know exactly what these organisms would have looked like back then, but they absolutely would have lived in the ocean, they would have been soft-bodied, and we presume they didn’t have a silica skeleton.”

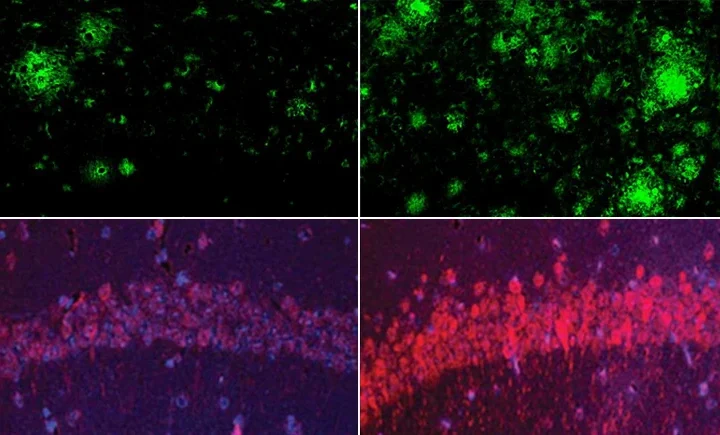

The research builds on the team’s 2009 findings, when they first discovered C30 steranes in rocks from Oman. That initial discovery faced skepticism, with some scientists suggesting the compounds could have come from algae or non-biological processes.

To address these doubts, the researchers expanded their search to rocks from western India and Siberia. They also conducted a series of experiments to verify their findings through multiple lines of evidence.

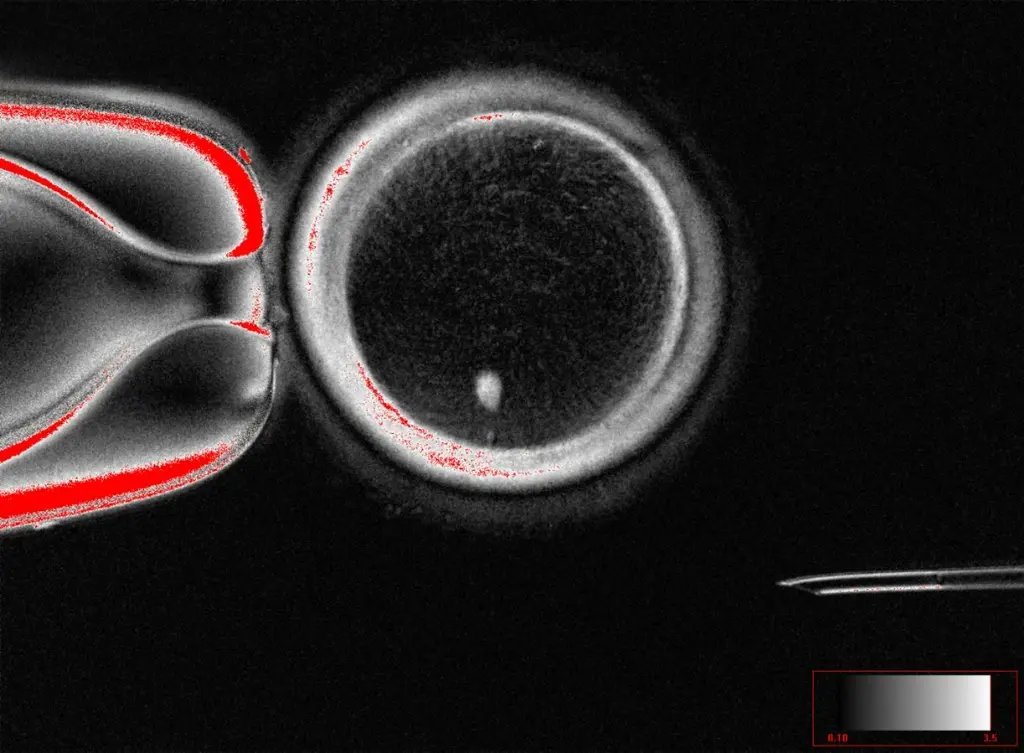

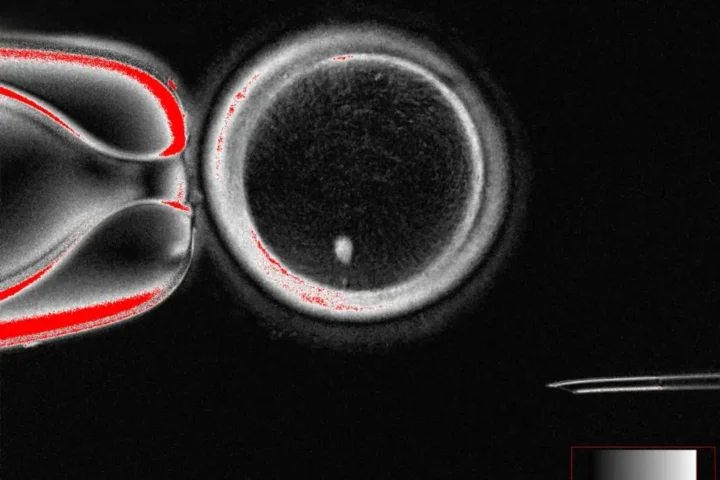

First, they examined modern demosponges and confirmed that these living creatures still produce the same rare C31 sterols – the biological precursors to the steranes found in ancient rocks.

Next, the team chemically synthesized eight different C31 sterols in the lab and simulated how these compounds would transform over hundreds of millions of years when buried and pressurized. Only two of these lab-created sterols matched exactly with the C31 steranes found in the rock samples. This pattern ruled out random geological processes as the source.

Similar Posts

“It’s a combination of what’s in the rock, what’s in the sponge, and what you can make in a chemistry laboratory,” Summons explains. “You’ve got three supportive, mutually agreeing lines of evidence, pointing to these sponges being among the earliest animals on Earth.”

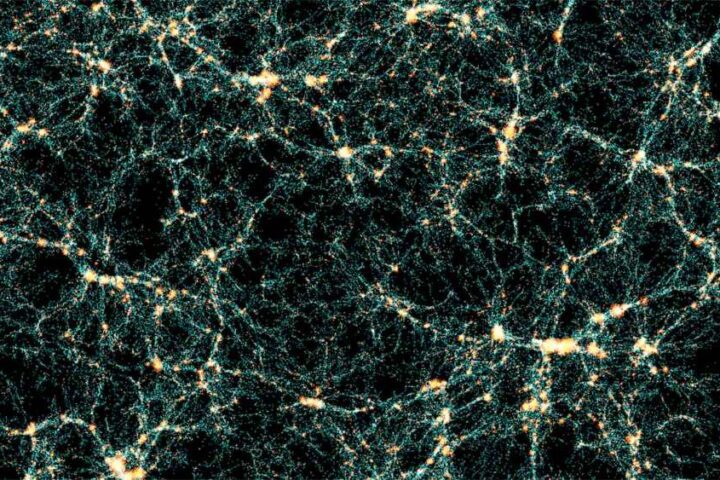

The findings support the theory that sponges were already thriving long before most other animal groups evolved. Unlike the more complex creatures that emerged during the Cambrian explosion, these early sponges would have been simple filter feeders without hard parts like skeletons.

This research also demonstrates a new standard for authenticating biomarkers – molecular traces of ancient life. “In this study we show how to authenticate a biomarker, verifying that a signal truly comes from life rather than contamination or non-biological chemistry,” Shawar notes.

The team plans to expand their search to rock samples from other regions to narrow down when exactly the first sponges – and therefore the first animals – appeared on Earth.

The study represents collaboration between researchers from multiple institutions including MIT, Caltech, University of California at Riverside, Cornell University, Uppsala University in Sweden, GeoMark Research in Houston, and the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry.

This research was supported by the MIT Crosby Fund, the Distinguished Postdoctoral Fellowship program, the Simons Foundation Collaboration on the Origins of Life, and the NASA Exobiology Program.