Children born to obese mothers face health problems even when they eat healthy diets. A new study from the University of Bonn shows why this happens. It reveals how a mother’s obesity can change liver cells in her baby before birth.

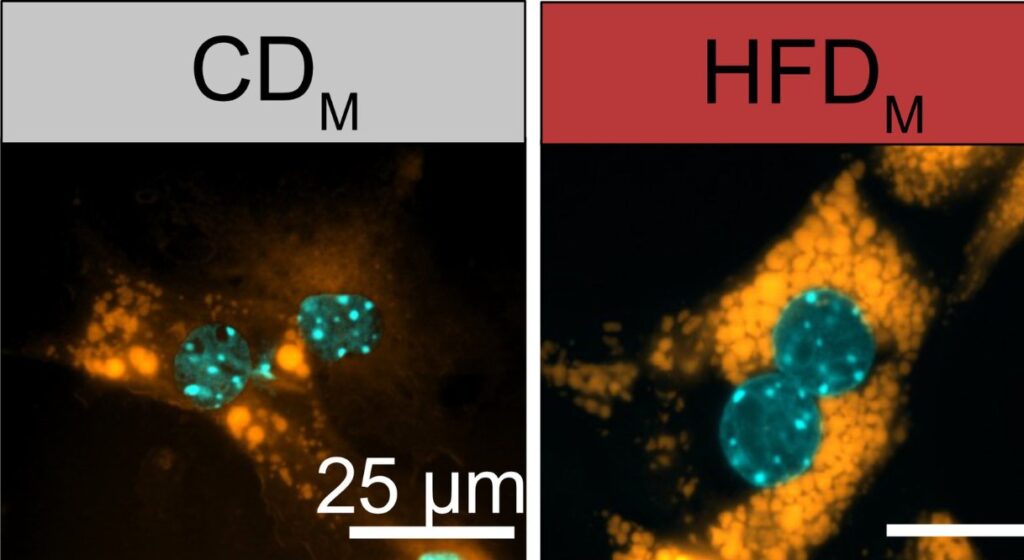

The research team found that maternal obesity changes special immune cells in the baby’s liver called Kupffer cells. These cells work like conductors, telling other liver cells what to do. When a mother is obese during pregnancy, these cellular conductors change their instructions.

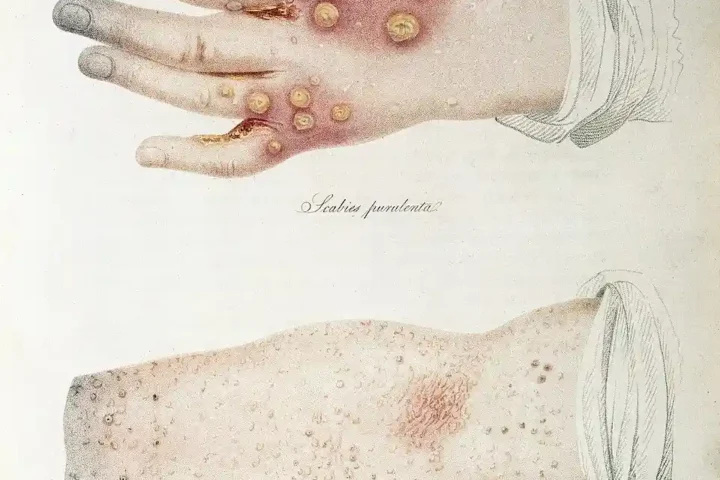

“We were able to show that the offspring of obese mothers frequently developed a fatty liver shortly after birth,” says Dr. Hao Huang, who worked on the study. “And this happened even when the young animals were fed a completely normal diet.”

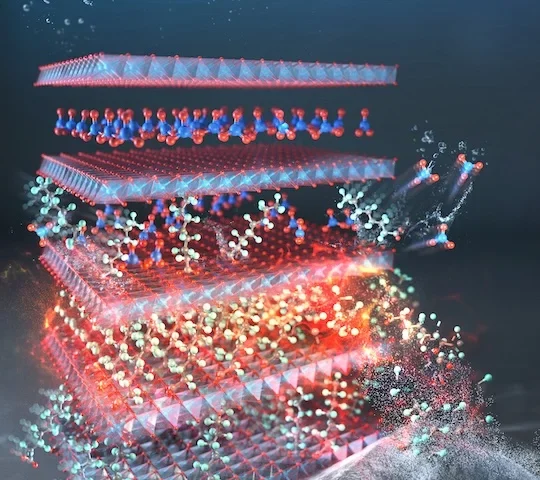

The scientists discovered that substances from obese mothers activate a switch in the baby’s Kupffer cells. This switch, called HIF1α, changes which genes are active in these cells. As a result, the Kupffer cells tell liver cells to store more fat.

When researchers removed this switch in Kupffer cells during pregnancy in mice, the babies did not develop fatty liver disease. This suggests doctors might someday prevent health problems from passing from mother to child by targeting this mechanism.

These findings matter for public health. Fatty liver disease begins with fat buildup but can lead to inflammation, scarring, and eventually liver damage. It also increases the risk of liver cancer.

This research adds to growing evidence that maternal obesity affects many body systems in children. Studies have linked mothers’ obesity to higher risks of obesity, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and asthma in their children. The effects happen through changes in immune function, gut bacteria, and gene activity.

Similar Posts

The impact goes beyond metabolism. Studies have found links between maternal obesity and brain development issues in children. The long-term effects are serious. Children of obese mothers have higher rates of fatty liver disease, Male offspring show more liver scarring – a dangerous progression of liver disease.

“It is becoming ever more evident that many diseases in humans already begin at a very early developmental stage,” notes Professor Elvira Mass, who led the research.

The study highlights why maintaining a healthy weight before and during pregnancy matters. Children of women who lose weight before pregnancy have lower risks of obesity and related conditions. With more than half of pregnancies in developed countries now involving overweight or obese women, these findings show the urgent need for better support for women before they become pregnant.

The University of Bonn team plans to study whether medications could target this mechanism. Such treatments could help break the cycle of obesity-related diseases passing from mothers to children.

As science reveals more about how early life shapes lifelong health, the message is clear: addressing maternal health helps not just one person, but future generations too.

Frequently Asked Questions

Maternal obesity reprograms special immune cells called Kupffer cells in the developing baby’s liver during pregnancy. These altered cells send different signals to liver cells, instructing them to store more fat regardless of the child’s own diet. This cellular reprogramming is activated by a molecular switch (HIF1α) that permanently changes gene expression patterns, leading to an increased risk of fatty liver disease even when children follow healthy eating habits throughout their lives.

Kupffer cells are specialized macrophages (immune cells) that reside in the liver. They act as “conductors” that direct surrounding liver cells on how to function. The University of Bonn research discovered that maternal obesity alters how these cells develop in the embryo, changing their signaling patterns. When reprogrammed by maternal obesity, they send inappropriate signals to liver cells, instructing them to accumulate more fat. This research is important because it identifies these cells as the specific mechanism through which a mother’s obesity affects her child’s liver health for life.

According to the research, 60% of female offspring born to obese mothers developed fatty liver disease compared to only 20% of those born to mothers with normal weight. This shows a three-fold increase in risk. Male offspring showed increased liver fibrosis (scarring), which is a dangerous progression of liver disease. With more than 50% of pregnancies in developed countries now involving women who are overweight or obese, this represents a significant public health concern affecting a large percentage of children.

This is not merely theoretical. The University of Bonn study demonstrated the mechanism through laboratory research using mice models. They observed that offspring of obese mothers developed fatty liver disease shortly after birth, even when fed a normal diet. When researchers genetically removed the HIF1α molecular switch in Kupffer cells during pregnancy, the offspring did not develop fatty liver disease, providing causal evidence for the mechanism. This research builds on numerous previous studies showing connections between maternal obesity and offspring health problems, but uniquely identifies the specific cellular mechanism involved.

The research offers hope for intervention. When scientists genetically removed the HIF1α molecular switch in Kupffer cells during pregnancy in mice, the offspring did not develop fatty liver disease. This suggests that targeting this mechanism could potentially prevent the transmission of obesity-related health problems from mother to child. The University of Bonn team is now investigating whether this mechanism could be targeted with medication in future studies. Additionally, weight management before pregnancy appears to be an effective preventative measure, as children of women who lose weight before pregnancy have shown reduced risks of obesity and related conditions.

Yes, research indicates that women who lose weight before pregnancy have children with significantly lower disease risks. Studies have shown that the offspring of formerly obese women who lost weight prior to conception have a reduced risk of developing obesity and metabolic disorders. This suggests that addressing maternal weight before pregnancy can help break the intergenerational cycle of metabolic disease. The findings highlight the importance of preconception health and provide a practical intervention point for reducing these risks.