The Price of Progress: Great Nicobar Island

Explore the environmental and human cost of India’s $10 billion mega-infrastructure project

The Great Nicobar Island Development Project proposes a massive transformation: a transhipment port, international airport, township, and power plant covering 166 square kilometers. This interactive tool reveals what will be lost in the process.

The southernmost tip of India sits on a knife’s edge. The Great Nicobar Island Development Project is a planned mega-infrastructure project for the southern tip of India’s Great Nicobar Island, in the Andaman Sea. What government planners call a Rs 72,000-75,000 crore “holistic development” initiative, critics describe as an ecological catastrophe in the making. The project envisions transforming this remote rainforest island into a bustling international shipping hub complete with a container port designed to handle 16 million TEUs annually in its final phase, an international airport, power plants, and townships that project documents project could accommodate several hundred thousand residents over a multi-decade build-out.

The controversy reached new heights when Congress leader Sonia Gandhi penned a scathing editorial calling the project a “grave misadventure” that threatens both indigenous communities and one of Earth’s last pristine ecosystems. “Our commitment to future generations cannot permit this large-scale destruction of a most unique ecosystem. We must raise our voice against this travesty of justice and this betrayal of our national values,” she said

Paradise at Risk: Understanding Great Nicobar’s Ecological Treasure

Great Nicobar spans about 910-920 square kilometers of mostly tropical rainforest in the southeastern Bay of Bengal. The island houses two national parks—Campbell Bay and Galathea—and forms part of a UNESCO-recognized biosphere reserve. The rainforests and beaches host numerous endangered and endemic species including the giant leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), the Nicobar megapode, the Nicobar crake (Rallina mayri), the Nicobar crab-eating macaque (Macaca fascicularis umbrosa), and the Nicobar tree shrew.

The waters around the island shelter coral reefs that scientists describe as irreplaceable. Galathea Bay, where much of the development would occur, serves as one of the most important leatherback nesting beaches in the northern Indian Ocean and the Andaman & Nicobar archipelago. These ancient mariners travel thousands of kilometers to lay their eggs on these specific beaches—a ritual that has continued for millennia.

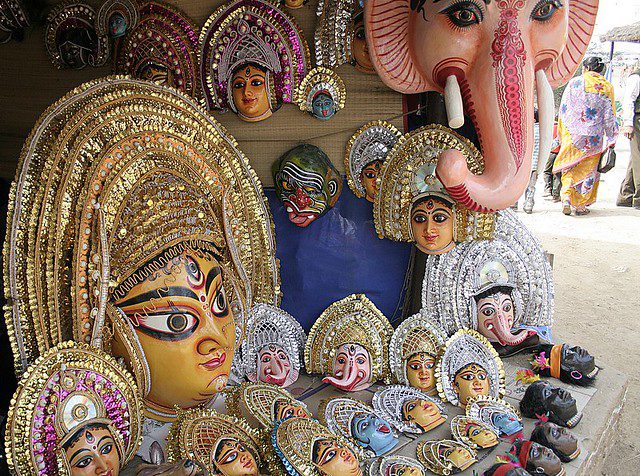

The Shompen’s Silent Crisis

Deep within Great Nicobar’s forests live the Shompen, one of the world’s most isolated peoples. The Shompen are designated as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group within the list of Scheduled Tribes. With a population estimated at around 200-300 individuals, they have survived for millennia as hunter-gatherers, maintaining minimal contact with the outside world.

To the Shompen, the forest ecosystem is central to their way of life and cultural practices. The project threatens to transform their world beyond recognition. The total population of the island is currently around 8,000-9,000, but the government’s project documentation and planning scenarios reference potential long-term build-out populations as high as 650,000 people over several decades.

In February 2024, 39 genocide experts from 13 countries issued a stark warning. “it will be a death sentence for the Shompen, tantamount to the international crime of genocide.” They explained that the Shompen have virtually no immunity to common diseases that outsiders carry. Even brief contact could trigger a population collapse—a pattern tragically repeated throughout history when isolated tribes encounter modern civilization.

The government’s response to these concerns includes what officials describe as “geo-fencing cum surveillance towers” to monitor the Shompen, among other mitigation measures. Critics argue this technocratic solution misses the fundamental point: the tribe’s survival depends on maintaining their forest ecosystem intact, not on surveillance.

Nicobarese Communities: Twice Displaced

The Nicobarese, another indigenous community of about 1,000 people on Great Nicobar, face their own crisis. Displaced from their ancestral lands following the cataclysmic Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami of December 2004, they have since been forced to live in government-provided shelters despite appeals to the local administration to be allowed to return.

They stated that they were completely dependent on forests in their original homes and they wanted to go back to foraging and tending to plantations on their lands, and rearing domestic animals, rather than working as manual labour in menial jobs, as they do at present. The project would permanently block their return, converting their ancestral villages into port facilities and townships.

The Tribal Council of Great and Little Nicobar Islands initially provided consent for the project in August 2022. However, three months later, they withdrew this consent upon learning that the development would destroy their pre-tsunami villages. Despite this formal withdrawal, the project has proceeded with clearances.

The Million-Tree Question

How many trees will fall to make way for this development? The answer reveals a troubling disconnect between official estimates and ecological reality. According to the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change estimates, 8.5 lakh trees may be cut for this project, which, the Congress MP stated, is a “depressing figure” which also can be a “gross underestimate”. She asserted that independent estimates suggest that 32 lakh to 58 lakh trees may eventually be cut.

The government maintains its figure of 850,000 trees, but ecologists argue this vastly underestimates the density of tropical rainforest. Some calculations based on actual forest density measurements suggest much higher numbers—though specific methodologies would need to be transparent to validate the upper-range estimates.

Compensatory Afforestation: The Great Swap Controversy

Perhaps nothing illustrates the project’s environmental contradictions more starkly than the compensatory afforestation plan. Due to this project, island will lose 12 to 20 hectares of mangrove cover, which the government will be compensating by afforestation in Haryana’s Aravallis as per rules which allow for such remote compensatory afforestation.

Think about that for a moment. Ancient rainforests and mangroves in a tropical island ecosystem will be “compensated” by planting trees in Haryana—a state 2,400 kilometers away with completely different climate, soil, and ecological conditions. Environmental scientists point out the obvious: you cannot recreate a rainforest ecosystem in the dry plains of North India.

The Rules specifically prohibit the creation of jungle safaris using one of the two components of the compensatory afforestation funds. While one component of the funds is meant to compensate for the loss of trees, the other component, called the net present value or NPV receipts, is supposed to compensate for the loss of other environmental services rendered by the forest, like groundwater recharge and biodiversity. Civil society documents and NGT notices allege that portions of the notified land were auctioned or proposed for mining.

Seismic Roulette in the Ring of Fire

Great Nicobar sits atop one of Earth’s most active seismic zones. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands lie on the boundary of the Indian and Burmese tectonic plates, part of the larger Sunda subduction zone — a highly active seismic belt resulting in frequent earthquakes and occasional tsunamis.

The 2004 tsunami serves as a permanent reminder of this vulnerability. The Galathea Bay area, where the port would be built, experienced permanent land subsidence of about 4-5 meters during that disaster. Sediment analysis from Badabalu beach in South Andaman revealed evidence of multiple large tsunami events over the past millennia, pointing to a long history of major seismic activity in the region.

Recent seismic activity underscores these concerns. A powerful earthquake measuring magnitude 6.2 struck near the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in July 2025. The region experiences dozens of felt earthquakes annually, reminding everyone that this is not a question of if another major earthquake will strike, but when.

Legal Shortcuts and Missing Voices

The draft Social Impact Assessment for the project reveals troubling gaps. The hearing that was held on June 29 to discuss the concerns of the ‘project affected community’ invited people from Gandhi Nagar and Shastri Nagar — two Gram Panchayats of Campbell Bay taluk of Nicobar district, where the government settled people from mainland India between 1968 and 1975. According to critics and local reporting, the indigenous Shompen and Nicobarese communities—those most affected—were not adequately consulted.

In fact, the draft SIA has been criticized by experts and tribal representatives for failing to adequately consult or assess impacts on the Shompen and Nicobarese; critiques say those communities are effectively missing from the SIA’s stakeholder analysis.

Strategic Imperatives vs. Ecological Reality

Proponents argue the project serves crucial strategic interests. Indira Point in the Galathea Bay, India’s southernmost point, is about 145 km north of Indonesia’s northernmost island, positioning it near the vital Malacca Strait through which much of global trade flows. The government envisions the port reducing India’s dependence on foreign transshipment hubs like Colombo and Singapore.

ANIIDCO issued EoIs for tree enumeration and other preparatory works in 2023-2024; project documents and presentations indicate phased implementation and that certain preparatory activities could begin in 2025.

Conservation Funds and Monitoring Committees

According to documents published by the project developer, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands Integrated Development Corporation Limited (ANIIDCO), the committees held their first joint meeting in April 2024 after being constituted in 2023. As per the minutes of the meetings, Rs. 88.69 crores has been sanctioned by the Ministry of Home Affairs for the preparation of conservation plans over the next year.

Wildlife institutes tasked with developing conservation plans state they need two years of field study just to understand what needs protecting. The conservation plans are expected to span 30 years—the same timeframe as the project itself. This raises an obvious question: how can you mitigate damage to an ecosystem you haven’t fully studied?

Coastal Zone Reclassification

In a significant development, the National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management (NCSCM) concluded the project no longer fell in a no-go fragile coastal zone, which could facilitate the development of the port. Previously, the area was classified as CRZ 1A, where most development is prohibited. The NCSCM now states the project area falls in CRZ 1B zone, where ports are allowed. The HPC report and ground-truthing details have not been fully disclosed publicly.

The Path Forward

Three monitoring committees have been set up to oversee that the Great Nicobar development project complies with the conditions of the Environment Clearance granted to it. Yet fundamental questions remain unanswered. Can surveillance towers protect the Shompen from diseases? Can trees planted in Haryana replace a tropical rainforest? Can coral reefs be successfully “translocated” as the government claims? Can massive infrastructure survive in one of Earth’s most seismically active zones?

The Great Nicobar project stands at the intersection of development ambitions and ecological preservation. Sonia Gandhi said, ‘The totally misplaced Rs 72000 crore expenditure poses an existential danger to the Island’s indigenous tribal communities.’ As tree enumeration begins and contractors prepare their bids, the window for reassessing this project narrows.

Conclusion

The article has examined the Great Nicobar Island Development Project’s multiple dimensions. The official environmental clearances and monitoring committees were reviewed. The project’s impact on the Shompen and Nicobarese communities was documented through tribal council letters and expert warnings. Tree-felling estimates ranging from 850,000 to several million were presented. The compensatory afforestation plan linking Nicobar’s rainforests to Haryana’s plains was described. Seismic risks in this active zone were outlined through recent earthquake data. The Social Impact Assessment’s exclusion of indigenous peoples was noted. Strategic rationales and conservation funding allocations were covered. These elements were drawn from government documents, tribal communications, ecological assessments, and seismic records.