The Arctic region is warming at a concerning pace. New findings indicate it’s heating more than three times faster than global averages. These insights come from recently published data by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

The numbers are striking. Arctic winter temperatures will likely rise by 2.4°C above recent averages over the next five years. This rate exceeds the worldwide temperature increase by more than 3.5 times.

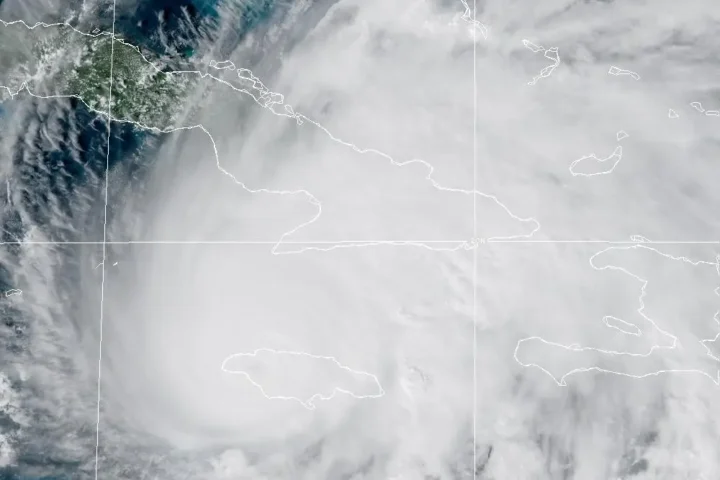

This rapid warming is melting sea ice at a concerning pace. The Barents Sea, Bering Sea, and Sea of Okhotsk will continue losing ice between 2025 and 2029. As ice disappears, the exposed darker ocean surface captures more solar heat rather than bouncing it back to space. This process creates a self-reinforcing cycle that intensifies warming further.

“We have just experienced the ten warmest years on record,” said WMO Deputy Secretary-General Ko Barrett. “Unfortunately, this WMO report provides no sign of respite over the coming years.”

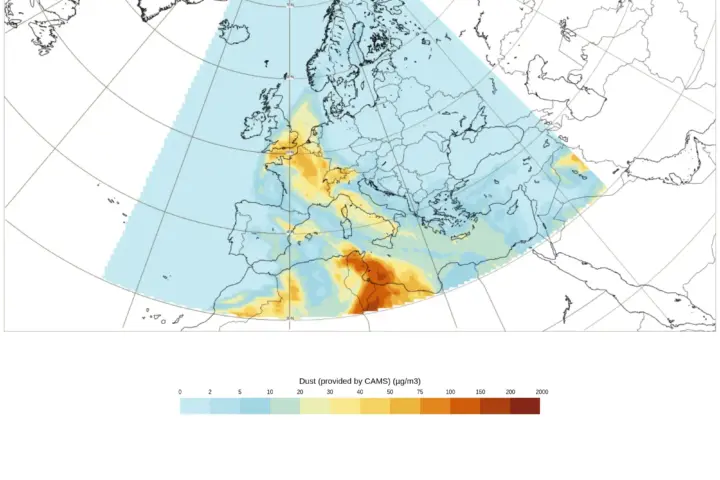

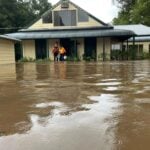

What does this mean for our daily lives? The melting Arctic ice disrupts global weather systems. This can lead to more extreme storms, floods, and droughts that damage homes, disrupt food production, and raise insurance costs.

The thawing permafrost in Arctic regions releases stored carbon and methane, further accelerating global warming. These changes might be pushing us toward climate tipping points – thresholds beyond which large, irreversible changes occur.

Similar Posts

The broader temperature outlook isn’t reassuring either. Scientists predict an 80% probability that at least one year before 2029 will exceed 2024’s record-breaking heat.

The world will likely breach the critical 1.5°C warming threshold set by the Paris Agreement. Scientists calculate an 86% likelihood that global temperatures will surpass this boundary during at least one of the upcoming five years.

Rainfall patterns are changing too. Northern Europe, Alaska, and parts of Africa will likely get wetter. The Amazon, however, faces drier conditions, threatening this vital ecosystem.

South Asia will probably continue seeing unusually wet years, except for patterns seen in 2023.

The WMO stresses this report should be a wake-up call before the COP30 climate conference in Brazil this November. Countries need to strengthen their climate commitments now.

“Continued climate monitoring and prediction is essential to provide decision-makers with science-based tools and information to help us adapt,” Barrett said.

The changes we’re seeing in the Arctic today will shape the climate challenges we all face tomorrow.