The Mexican gray wolf, an endangered subspecies vital to Southwestern ecosystems, has experienced declining genetic diversity for the fourth consecutive year, even as their numbers in the wild have reached 286 animals.

Thirty conservation organizations recently warned that this genetic crisis threatens the wolves’ recovery and called for urgent changes to management approaches. The captive wolf population maintains 37% more genetic diversity than their wild counterparts, highlighting a critical gap that puts the species’ long-term survival at risk.

“Mexican wolves won’t recover unless agencies restore as much genetic diversity as can be salvaged from what’s already been squandered,” said Michael Robinson from the Center for Biological Diversity. “Federal and state agencies need to stop killing wolves with important genes.”

The wolves face two major management challenges. First, the cross-fostering program, where captive-born pups are placed in wild dens, has shown limited success. Only 24 of 99 cross-fostered pups released through 2023 survived through their birth year. Second, since April 2025, agencies have removed seven genetically rare wolves from the wild, including shooting a pregnant female in Arizona and a pup in New Mexico.

Similar Posts

Conservation groups are pushing for a return to family pack releases, which were last conducted in 2006 with the Meridian pack. These releases proved highly successful, with genetic diversity peaking in 2008 after those pups matured and bred.

“The wild lobo population needs genetic help, and releasing family packs of wolves from captivity is clearly the best way to provide that,” said Chris Smith of WildEarth Guardians.

Another key issue is the Interstate-40 boundary that prevents Mexican wolves from traveling north and northern gray wolves from moving south. This artificial barrier blocks natural wolf dispersal that could help restore genetic diversity.

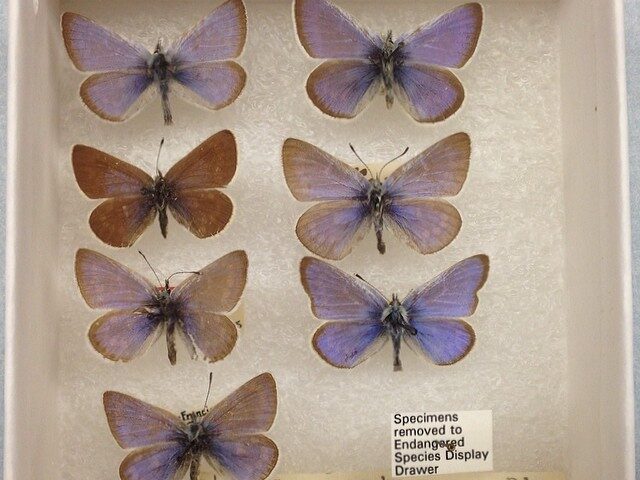

All wild and captive Mexican wolves descend from just seven founding animals – six from Mexico and one from Arizona. The limited genetic pool has led to inbreeding problems including lower reproductive rates, nasal carcinomas, and fused toes.

In August 2025, following pressure from 8,000 citizens and 36 organizations, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service released a captive-born family – Asha and her mate Arcadia with five pups – at Ladder Ranch. Meanwhile, several New Mexico counties have declared “states of emergency” concerning wolves, which conservationists warn could undermine recovery efforts.

“If not addressed, the ever-dropping diversity of the lobo genome will ultimately doom the Mexican gray wolf,” said Mary Katherine Ray, wildlife chair for the Rio Grande chapter of the Sierra Club.

For these wolves to recover, conservation groups recommend resuming family pack releases, stopping the removal of genetically valuable wolves, allowing occasional mating with northern gray wolves, ending the rigid I-40 dispersal barrier, and protecting cross-border dispersers.