New research from the University of Ottawa reveals that women under 49 and over 75 face higher death rates from breast cancer due to relying on symptom detection rather than regular screening.

The study found that patients whose breast cancers were detected through symptoms had a 63% higher chance of dying from breast cancer compared to those whose cancers were found through routine screening. They were also 6.6 times more likely to have advanced cancer at diagnosis.

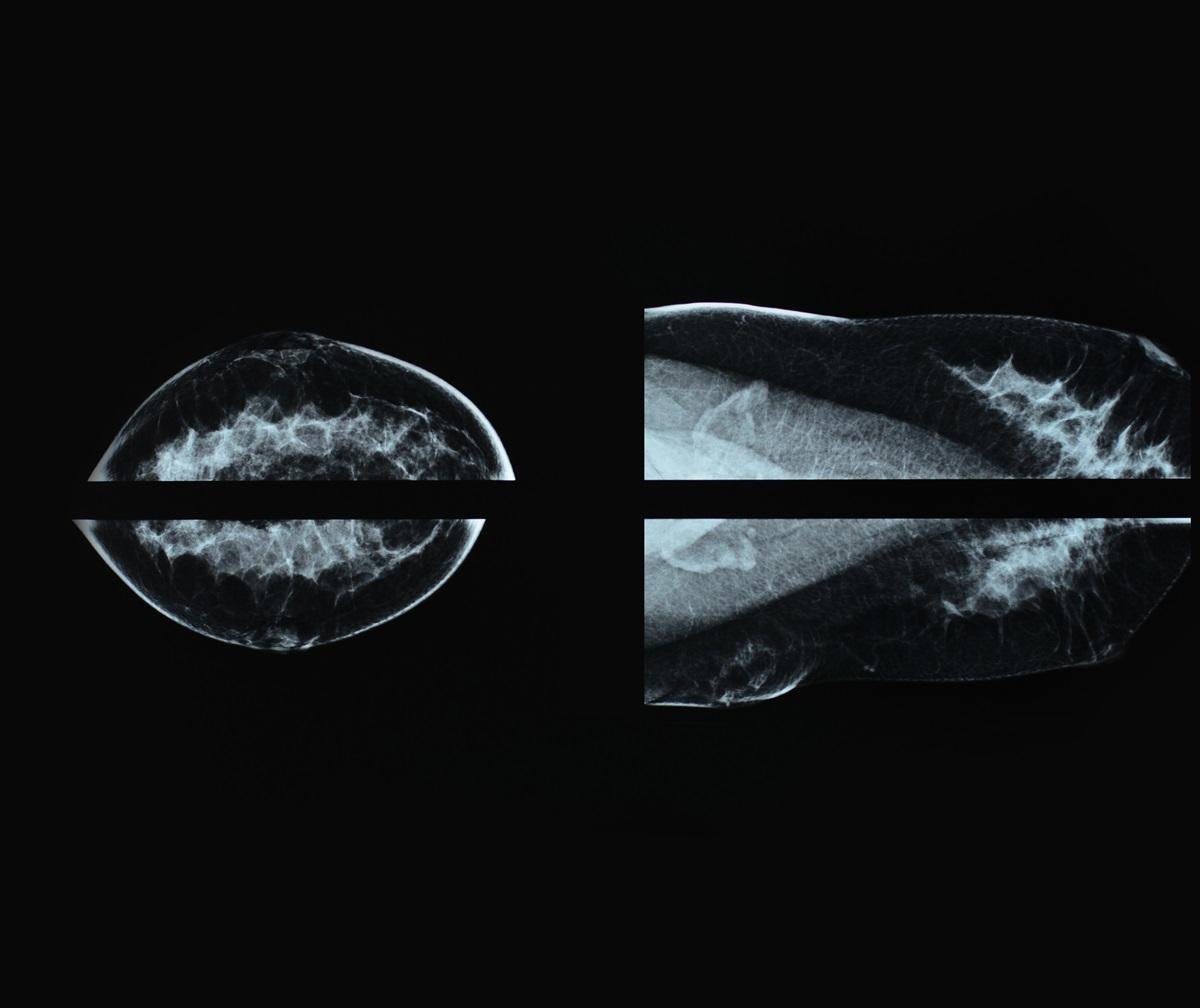

“What is most surprising is how many people died within the short period after their breast cancer was detected,” explains Dr. Jean Seely, Head of Breast Imaging at The Ottawa Hospital and professor of radiology at uOttawa. “That 50 percent of cancers were detected because of symptoms was also much higher than expected.”

This research challenges current Canadian screening guidelines, which typically recommend mammograms only for women aged 50-74. The findings suggest that extending screening to younger and older women could save lives.

The results are particularly concerning for specific age groups. Among women aged 40-49 with breast cancer who died, a staggering 91.7% had symptom-detected cancers. For women over 75, symptom-detected cancers accounted for 39.6% of breast cancer deaths.

Dr. Seely, who has documented the benefits of early detection for women in their forties, points out that cost concerns about expanding screening are misguided. “Costs are often cited as a determining factor in not screening at an earlier age. But this rationale is erroneous since these costs are lower compared to treating breast cancer at advanced stages.”

Similar Posts

The financial argument for broader screening is compelling. Previous research from uOttawa found that early cancer screening could save the Canadian healthcare system nearly half a billion dollars over patients’ lifetimes, while preventing 3,499 breast cancer deaths.

Women whose cancers were found through symptoms often required more intensive treatments. They were more likely to need mastectomies (complete breast removal) rather than lumpectomies (removal of just the tumor), and more frequently underwent chemotherapy.

This has significant implications for Canadian health policy. While the United States recently updated its guidelines to recommend screening for women starting at age 40, Canada’s national guidelines still focus on the 50-74 age range, though practices vary by province.

For women, the message is clear: discussing screening options with healthcare providers, regardless of age, could be lifesaving. Factors beyond age, such as family history and breast density, can influence individual screening needs.

Nearly 20% of the 821 breast cancer patients in the study died within about seven years of follow-up, with half of these deaths directly attributable to breast cancer.

The study, published in Radiology: Cancer Imaging, reinforces the life-saving impact of proactive screening over waiting for symptoms to develop, especially for those outside current guideline recommendations.