About a thousand years ago, Pacific islanders embarked on what might be called one of history’s most remarkable climate-driven migrations. Instead of simply enduring increasingly dry conditions, these seafaring communities did something remarkable – they sailed east, following the rain.

New findings from British researchers show that a massive rainfall band in the South Pacific moved eastward approximately 1,100–400 years ago (≈ 925–1625 CE), transforming the region’s water availability and likely influencing human settlement patterns.

“People in the region were effectively chasing the rain eastwards,” explains Professor David Sear from the University of Southampton, Principal Investigator for PROMS, who led the research alongside University of East Anglia (UEA) colleagues.

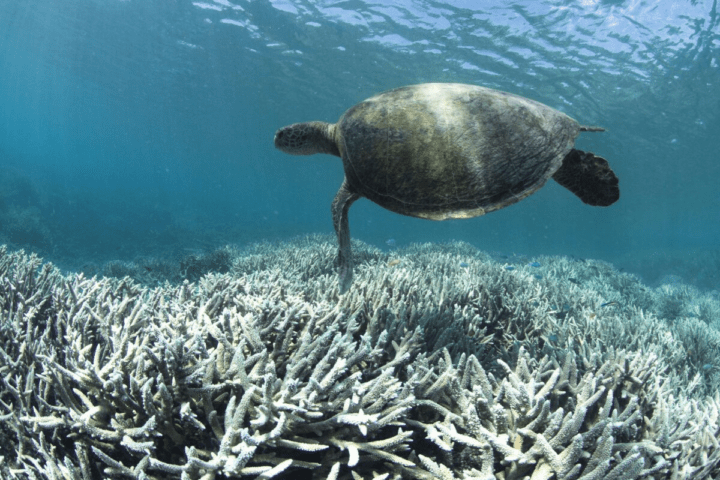

This giant rainfall band, known as the South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ), stretches over 7,000 kilometers from Papua New Guinea past the Cook Islands. When it shifted, islands in Western Polynesia like Samoa and Tonga grew drier, while Eastern Polynesian islands including Tahiti and Nuku Hiva received more rainfall.

The research team extracted mud samples from lake and swamp bottoms in Tahiti and Nuku Hiva. These sediment cores contained preserved plant waxes – tiny fatty substances that once coated ancient leaves. By analyzing these waxes, scientists determined rainfall patterns from centuries ago.

“Water is essential for people’s survival,” notes Dr. Mark Peaple from the University of Southampton. “If this vital resource was running low, it’s logical that populations would follow it and colonize areas with more reliable water security – even if this meant venturing across vast ocean stretches.”

The timing tells a compelling story. Archaeological evidence places the final wave of Eastern Polynesian settlement around 1,000 years ago – precisely when the rainfall shift was underway. This suggests a practical reason behind one of humanity’s most impressive migration journeys.

Scientists describe this as a “push-pull” scenario – drying western islands pushed people to leave, while increasingly wet eastern islands pulled settlers toward new opportunities.

What caused this massive rainfall shift? Researchers point to natural changes in ocean surface temperatures across the Pacific, which gradually moved the rain band eastward over several centuries.

Similar Posts

The research team combined their plant wax analysis with other rainfall records from across Polynesia and sophisticated climate model simulations. This approach allowed them to pinpoint when and where rainfall patterns changed, and what likely triggered these shifts.

“Bringing together knowledge from paleoclimate archives and climate models has given us key insights into how and why a critically understudied region changed over the last 1,500 years,” explains Dr. Daniel Skinner from UEA.

Professor Manoj Joshi from UEA adds: “By better understanding how larger-scale climate changes affected the South Pacific over past millennia, we can build better predictions for how future climate change will affect the region.”

The study highlights an often-overlooked aspect of human history – how environmental changes influence migration and settlement patterns. For these ancient Pacific communities, following the rain meant survival.

This research emerged from a collaboration called PROMS (Pacific Rainfall over Millennial Timescales) between the University of Southampton and UEA. The UK’s Natural Environment Research Council funded the work, with additional fieldwork support from National Geographic Explorer grants.

The findings appear in the scientific journal Communications Earth and Environment*, shedding new light on how climate influenced one of humanity’s most remarkable migration stories.