The sight of children wearing glasses has become increasingly common in schools worldwide. Currently, 35% of children have myopia, or near sightedness, and experts project this number could reach 40% by 2050 – affecting over 740 million children globally.

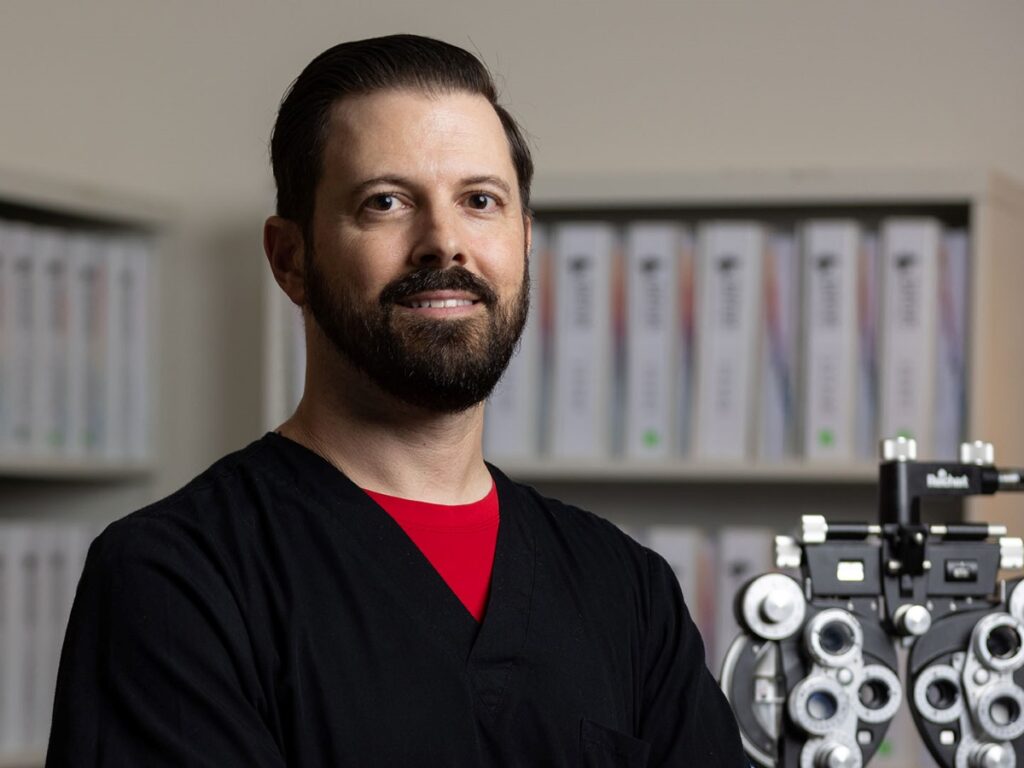

These alarming statistics motivated Dr. David Berntsen at the University of Houston College of Optometry and his collaborators at Ohio State University to find better solutions. Their groundbreaking research, known as the BLINK Study (Bifocal Lenses In Nearsighted Kids), has revealed that high-add power multifocal contact lenses effectively slow myopia progression in children, with benefits lasting even after older children stop wearing them.

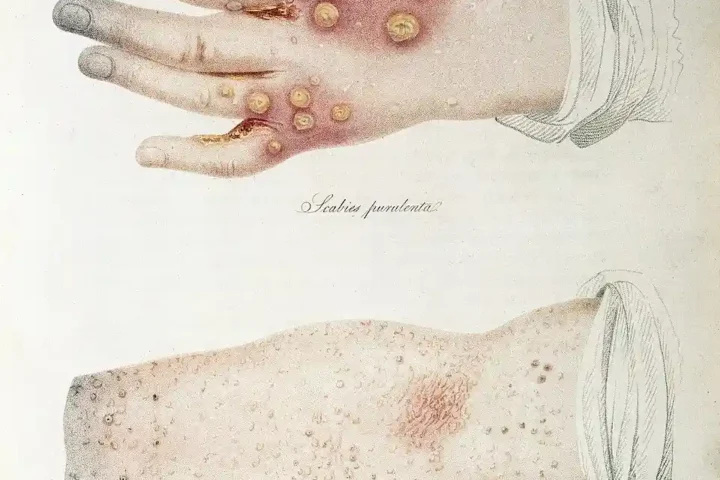

Myopia happens when a child’s eyes grow too long from front to back. This causes light to focus in front of the retina instead of directly on it, making distant objects appear blurry. Without proper treatment, myopia typically worsens throughout childhood as the eye continues to grow improperly.

For decades, eye doctors have simply prescribed stronger glasses or contacts as myopia worsened, without addressing the underlying problem of excessive eye growth. This approach left many children developing high myopia, which increases their risk of serious eye problems later in life.

Before the BLINK studies, eye care professionals had limited options for slowing myopia progression. Low-dose atropine eye drops showed some effectiveness but often caused a “rebound effect” when discontinued. Orthokeratology – rigid lenses worn overnight to temporarily reshape the cornea – helped some children but wasn’t suitable for everyone.

Dr. Berntsen’s team wanted to understand exactly how multifocal contact lenses work biologically. Their latest research, published in Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science, revealed the answer lies in the choroid – a layer of blood vessels that supplies the retina with oxygen and nutrients.

“We evaluated changes in subfoveal choroidal thickness and area in children wearing soft multifocal contact lenses for myopia control,” Dr. Berntsen reported. The team discovered that children wearing high-add multifocal lenses experienced a slight thickening of the choroid, and these same children showed slower eye growth.

Similar Posts

“While there were no changes in choroidal thickness or area in the single vision group, eyes in the high-add multifocal contact lens group that grew less maintained a slightly thicker choroid throughout the three years of multifocal lens wear,” explained Dr. Berntsen.

The study included 281 myopic children aged 7 to 11 years who were randomly assigned to wear either standard single vision contact lenses or multifocal contact lenses.

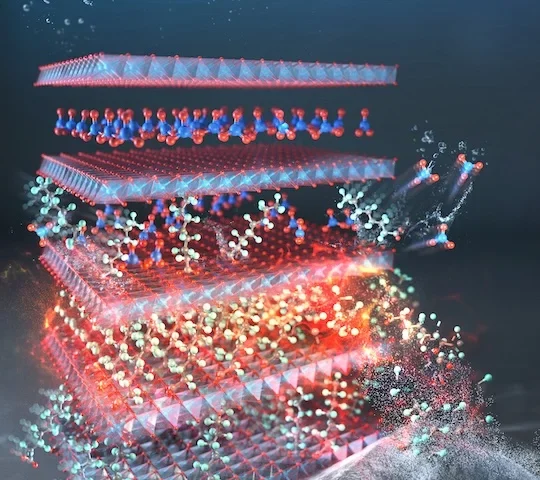

Multifocal contacts work differently than regular lenses. They have a central zone that corrects distance vision, surrounded by outer rings that create what scientists call “myopic defocus” in the peripheral retina. This design essentially tricks the eye into slowing its growth. Traditional glasses and contacts might actually worsen myopia by creating “hyperopic defocus” in peripheral vision, which can stimulate more eye growth.

Most importantly, the BLINK study showed that increased choroidal thickness after just two weeks predicted less eye elongation over the entire three-year study period. This finding gives eye doctors a potential early indicator of which children will respond best to this treatment.

Jeffrey J. Walline, associate dean for research at Ohio State University College of Optometry and BLINK2 study chair, highlighted another significant discovery: “These follow-on results from the BLINK2 Study show that the treatment benefit with myopia control contact lenses have a durable benefit when they are discontinued at an older age.”

For worried parents watching their children’s vision worsen with each eye exam, this research offers real hope. By starting treatment early with multifocal contacts, children might avoid the serious complications associated with high myopia later in life, such as retinal detachment, myopic macular degeneration, glaucoma, and cataracts.

The BLINK studies, funded by the National Eye Institute, represent a fundamental shift in how we approach childhood myopia – moving from simply correcting blurry vision to actively managing and slowing the condition’s progression to protect lifelong eye health.

Frequently Asked Questions

Myopia, or nearsightedness, is a vision condition where distant objects appear blurry while close objects remain clear. It occurs when the eye grows too long from front to back, causing light to focus in front of the retina instead of directly on it. This condition has reached epidemic proportions, currently affecting 35% of children worldwide and projected to affect 40% (over 740 million children) by 2050. Beyond requiring corrective eyewear, high myopia increases the risk of serious eye conditions later in life, including retinal detachment, glaucoma, and cataracts.

Multifocal contact lenses have a unique “bullseye” design that standard glasses and contacts don’t have. The central zone corrects distance vision, while the outer concentric rings add focusing power to create what scientists call “myopic defocus” in the peripheral retina. Regular single-vision lenses focus peripheral light behind the retina (hyperopic defocus), which may actually stimulate more eye growth and worsen myopia. In contrast, multifocal lenses send signals to the eye to slow its growth, addressing the underlying cause of myopia rather than just correcting symptoms.

The BLINK study demonstrated that children as young as 7 years old can successfully wear and benefit from multifocal contact lenses. The research included children aged 7-11, and found that starting treatment at a younger age led to greater benefits in slowing myopia progression. Children in this age range were able to achieve optimal visual acuity and adapt to wearing multifocal lenses much like they would with single vision contact lenses, making it a viable option for younger children with proper supervision and care.

According to the BLINK study, high-add multifocal contact lenses slowed myopia progression by approximately 43% over three years compared to single vision contact lenses. Even more importantly, the BLINK2 study showed that these benefits continue even after children stop wearing the lenses, unlike other treatments that often show a “rebound effect” where myopia worsens after discontinuation. The study revealed that increased choroidal thickness after just two weeks of wearing these lenses was associated with less axial elongation over the entire three-year study period.

Several alternatives exist for myopia control, including: 1) Low-dose atropine eye drops, which have shown effectiveness but may cause a “rebound effect” after discontinuation; 2) Orthokeratology (Ortho-K), which involves rigid gas permeable lenses worn overnight to temporarily reshape the cornea; 3) Specialized myopia control spectacle lenses that incorporate peripheral defocus technology; and 4) Lifestyle modifications such as increasing outdoor time and reducing near-work activities. The BLINK studies suggest multifocal lenses may have advantages over some alternatives, particularly regarding the lasting benefit without rebound effects.

While contact lenses are generally safe for children when properly fitted and cared for, potential risks include eye infections, corneal abrasions, and allergic reactions. However, the BLINK study demonstrated that children as young as 7 years old could safely wear contact lenses with proper supervision and education on lens care. Parents should ensure regular follow-up appointments with eye care professionals, maintain strict hygiene practices, and teach children proper lens handling. The potential benefits of slowing myopia progression and reducing the risk of serious eye conditions later in life may outweigh these manageable risks for many children.