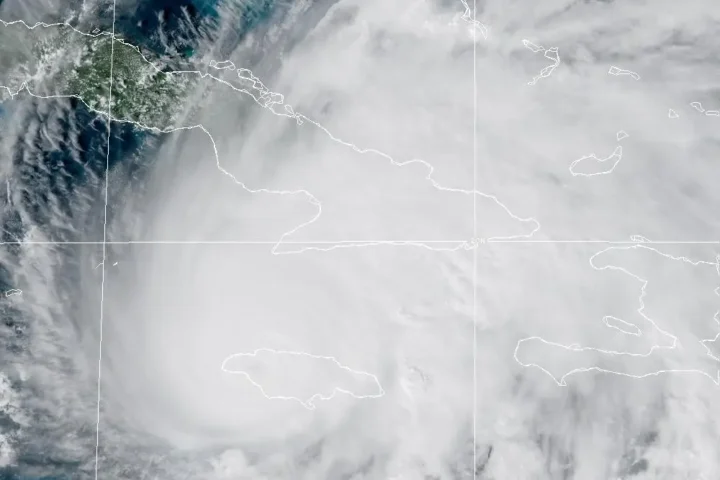

Hurricane Erin kept its distance but left Jersey Shore beaches battered and bruised. Crews are working at low tide to reopen paths before Labor Day visitors arrive.

Beach entrances turned treacherous after Erin carved six-to-eight-foot drops in the sand. Upper Township lost 15-20 feet of dunes from powerful offshore waves.

“We lost a ton of beach here, these dunes were probably 20 feet,” Dan McDonough from Riverside told reporters. “That bad night of all the waves hitting it, it just kept taking the sand out.”

The damage runs from Monmouth County to Cape May, with “scarping” – the technical term for those vertical sand cuts – changing beach shapes along the coast.

Public Works crews use bulldozers at every low tide to rebuild beach access. Strathmere had 12 entrances closed because of dangerous drop-offs.

More Posts

“Every low tide, we can come out and harvest sand to create an access path,” Upper Township Mayor Curtis Corson explained.

Beach Patrol Chief Bill Handley noted the safety concerns: “Right now, to be honest with you, it’s not safe with all these cliffs and the drop-offs going to the beach.”

The worst damage happened in specific areas that scientists track closely.

Kim McKenna from Stockton University’s Coastal Research Center identified vulnerable locations as “erosion hot spots areas adjacent to inlets” – places where water flows between barrier islands.

The New Jersey DEP confirmed notable erosion “primarily along the southern three-fourths of the coast” though beaches did protect property as designed.

Strathmere experienced severe erosion with officials estimating 15-20 feet of dune loss in Upper Township. Ocean City saw dune damage between 4th and 11th Streets with waves reaching under the Boardwalk.

Atlantic City beaches lost sand, especially north of St. James Place. North Wildwood’s dune paths suffered damage, while Wildwood had “ponding” – seawater pooling between the boardwalk and dunes.

In Cape May, waves pushed over dunes onto Beach Drive at Wilmington Avenue.

The damage comes as politicians argue over beach money. A proposed bill would cut Army Corps beach replenishment from $200 million to $60 million next year.

Rep. Frank Pallone says this threatens decades of consistent funding, while Rep. Jeff Van Drew plans to introduce legislation for “permanent and reliable” beach project money.

Rep. Pallone said small shore towns can’t foot the bill alone.

Beach projects do more than keep tourists happy – they protect coastal homes.

“Just having a big beach for tourism is really a plus, but they’re really designed for protecting homes,” McKenna explained. Without replenishment, properties face greater storm risks.

New Jersey’s NJBPN includes 171 profile sites surveyed twice yearly since 1986. This monitoring helps identify vulnerable areas before storms hit.

Some damaged paths were reopened, with more targeted before Labor Day. Visitor Marina Radvinsky described how her children used boogie boards to slide down the newly formed steep slopes at Vincent Avenue in Strathmere.

“We were definitely worried about our vacation,” she said, pleased with the quick repairs.

Jersey Shore towns face a sobering fact: hurricane season peaks between mid-August and mid-October, just starting its most active phase.

With narrower beaches and damaged dunes, the shore remains vulnerable. As veteran lifeguard Kip Emig put it: “We are back to where we were in the beginning of May. Some beaches lost all the buildup that we naturally get in summer.”

The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection completed a preliminary assessment and will post a final Coastal Storm Survey & Damage Assessment report within several days.