Climate change isn’t just making the planet hotter – it’s turning food production into a rollercoaster ride of unpredictable harvests that threatens global food security.

A new study led by the University of British Columbia reveals that warming temperatures are causing more dramatic swings in yearly crop yields, creating a pattern of boom-and-bust harvests that pose serious challenges for farmers and food systems worldwide.

“Farmers and the societies they feed don’t live off of averages—they generally live off of what they harvest each year,” said Dr. Jonathan Proctor, assistant professor at UBC’s faculty of land and food systems and the study’s lead author. “A big shock in one bad year can mean real hardship, especially in places without sufficient access to crop insurance or food storage.”

The research, published in Science Advances, shows that for every 1°C of warming, year-to-year variability in yields increases significantly: 7% for corn, 19% for soybeans, and 10% for sorghum. While previous studies focused on declining average yields, this new research highlights the growing instability in food production.

This increased volatility means that once-rare crop failures are becoming much more common. With just 2°C of warming above current temperatures, soybean failures that historically happened once every century would occur every 25 years. For corn, such failures would jump from once-in-a-century to once every 49 years, and for sorghum, once every 54 years.

If greenhouse gas emissions continue unchecked, the situation worsens dramatically – soybean failures could happen as frequently as every eight years by 2100.

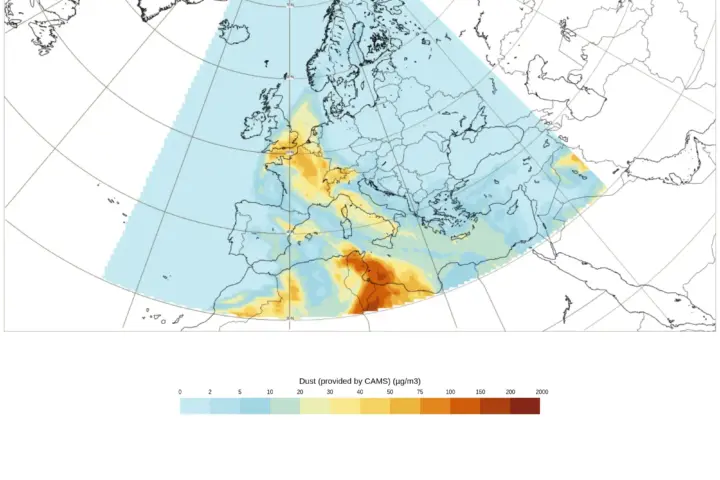

The regions facing the highest risks often have the fewest resources to cope. Parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, Central America, and South Asia are particularly vulnerable, as many farms in these areas rely entirely on rainfall and have limited financial safety nets.

But even wealthy nations aren’t immune. In 2012, a heatwave and drought in the U.S. Midwest caused corn and soybean yields to drop by about 20%, costing billions in losses. The impact rippled through global markets, pushing food prices up by nearly 10% within months.

Similar Posts

The researchers identified a “double whammy” driving these wild swings: heat and dryness increasingly occurring together. Hot weather dries out soil, and dry soil makes heatwaves worse by allowing temperatures to rise more quickly – a vicious cycle intensified by climate change.

Dr. Proctor explains this relationship with a simple comparison: “If you’re hydrated and go for a run your body will sweat to cool down, but if you’re dehydrated you can get heatstroke. The same processes make dry farms hotter than wet ones.”

Even brief periods of these combined stresses can devastate crops – disrupting pollination, shortening growing seasons, and pushing plants beyond recovery. For soybeans and sorghum especially, this growing overlap between heat and moisture shortage explains much of the increase in yield volatility.

Irrigation can help reduce this instability where water is available. However, many high-risk regions already face water shortages or lack irrigation infrastructure.

The study’s authors call for urgent investment in several solutions: developing heat- and drought-resistant crop varieties, improving weather forecasting, implementing better soil management practices, and strengthening safety nets like crop insurance.

However, they emphasize that cutting greenhouse gas emissions remains the most effective way to limit these increasingly erratic harvest patterns that threaten global food security.

“Not everyone grows food, but everyone needs to eat,” noted Dr. Proctor. “When harvests become more unstable, everyone will feel it.”