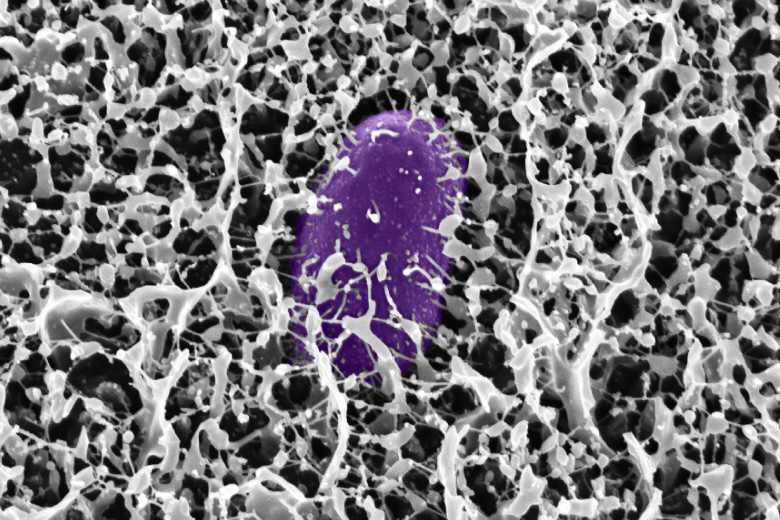

Scientists at MIT have discovered that mucus does more than just create mess when you’re sick. It contains powerful molecules called mucins that can stop dangerous Salmonella bacteria from making people ill.

The research team, led by Professor Katharina Ribbeck, found that specific mucins in our digestive system act as natural defenders against Salmonella. This bacteria causes about 1.35 million infections in the United States each year.

“This approach could provide a low-cost solution to a major global health challenge that costs billions annually,” says Ribbeck.

The scientists identified two types of mucins that protect us. MUC2, found in our intestines, and MUC5AC, found in our stomach, work by shutting down a master control switch in Salmonella called HilD. When this switch is turned off, the bacteria can’t use the tools it needs to invade our cells and cause infection.

Salmonella is a serious health problem worldwide. The World Health Organization reports it causes about 93 million cases of gastroenteritis and 155,000 deaths globally each year. In the U.S. alone, it leads to 26,500 hospitalizations and 420 deaths annually, mostly from contaminated food.

Similar Posts

MIT researchers now hope to create synthetic versions of these protective mucins that could be added to oral rehydration salts or made into chewable tablets. These products could help prevent infections in travelers visiting regions where Salmonella is common or protect soldiers in areas with poor sanitation.

“Mucin mimics would particularly shine as preventatives, because that’s how the body evolved mucus – as part of this innate immune system to prevent infection,” explains Kelsey Wheeler, an MIT Research Scientist who led the study.

This approach is especially promising because it doesn’t rely on antibiotics. With more Salmonella becoming resistant to antibiotics, finding new ways to prevent infection is crucial.

The research builds on earlier work showing that mucins can also disarm other harmful germs like those that cause cholera and lung infections.

Studies in mice have shown that Salmonella tends to infect parts of the digestive tract with little or no mucus protection. This suggests that boosting the mucus barrier in these vulnerable areas could prevent illness. This approach could help millions who suffer from travelers’ diarrhea and foodborne illness each year, especially in regions with limited healthcare resources.