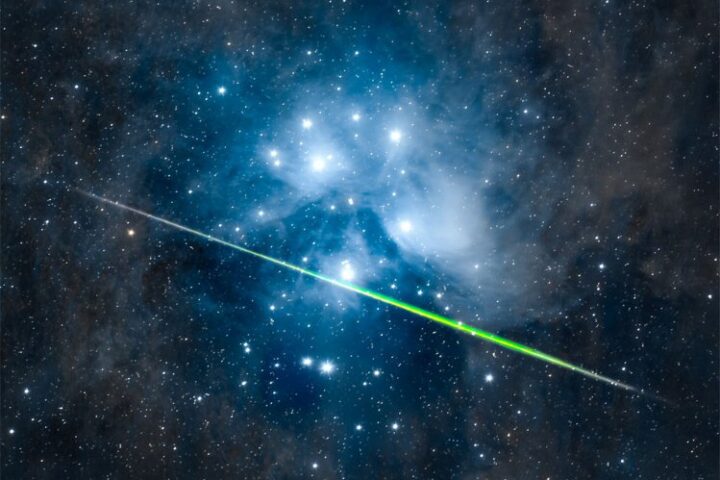

A star located about 3,000 light-years away from Earth did something remarkable between late 2024 and early 2025 – it dimmed by a staggering 97%, nearly vanishing from view before brightening again. Scientists have now figured out what caused this rare event. ASASSN-24fw, an F-type star about twice the size of our sun, puzzled astronomers when it began fading in September 2024. After being stable for over a decade, the star’s brightness dropped dramatically during an eight-month period before returning to normal in May 2025.

“We explored three different scenarios for what could be going on,” said Raquel Forés-Toribio, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at Ohio State University. “Evidence suggests it is likely that there is a cloud of dust in the form of a disk around it.”

What makes this case particularly interesting is that the star’s color remained unchanged during its dimming phase. This key clue helped researchers determine that the star itself wasn’t changing but was instead being blocked by something in front of it – a large disk of dust and gas.

This dusty disk is estimated to be about 1.3 astronomical units across – larger than the distance between Earth and the Sun. The disk likely contains large clusters of carbon or water ice particles similar in size to large dust grains found on Earth.

But the dust disk alone doesn’t explain everything. The researchers believe ASASSN-24fw is actually part of a hidden binary system – two stars orbiting each other. A smaller, cooler companion star may be driving the changes in geometry that caused the dramatic eclipse.

“At this moment, with the data that we have, what we propose is that there should be two stars together in a binary system,” Forés-Toribio explained. “The second star, which is much fainter and less massive, may be driving the changes in geometry leading to the eclipses.”

Similar Posts

Such dramatic dimming events are extremely rare. “We were hoping to find some similarities and we didn’t really find very many, which is interesting in and of itself,” said Chris Kochanek, co-author and professor of astronomy at Ohio State, who described the event as “one-in-a-million.”

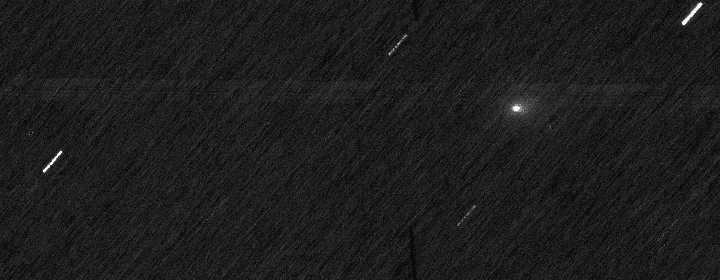

The star was discovered by the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASAS-SN), a network of small telescopes that monitor the entire visible night sky. Since its establishment over a decade ago, ASAS-SN has collected about 14 million images of the cosmos.

Based on historical data, researchers believe this star experiences eclipses approximately once every 43.8 years, with the next major dimming not expected until around 2068.

“The universe’s capacity to surprise us is continuous,” said Krzysztof Stanek, another co-author and professor of astronomy at Ohio State. “Even with small telescopes on the ground and big telescopes in space, every time we get a new capability, we still discover new things.”

The team plans to continue observing the system using more powerful instruments, including the James Webb Space Telescope and the ground-based Large Binocular Telescope, to better understand the composition and structure of the dust disk.

“This study is a particularly interesting example of a broader class of still very strange objects,” Stanek added. “We learn more about astrophysics when we find things that are unusual, because it pushes our theories to the test.”