Thousands of years ago, humans made a dangerous journey across the icy Bering Strait into the Americas. Now, scientists have discovered these ancient travelers carried something unexpected – a piece of DNA from extinct Denisovans that may have helped them adapt to their new home.

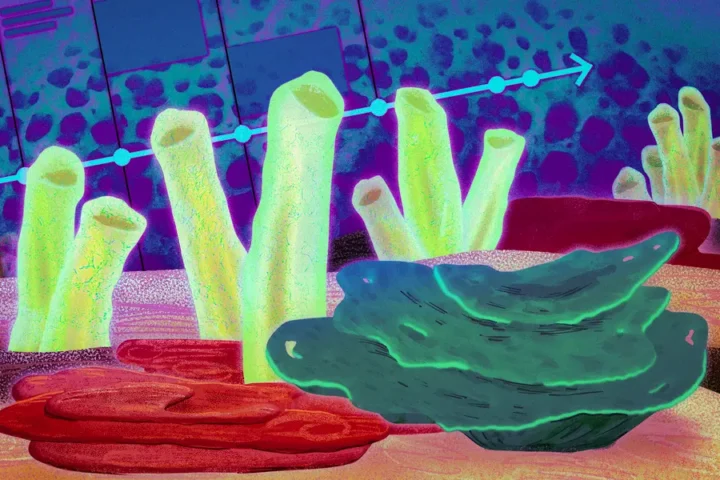

A new study published August 21, 2025, in Science shows that a gene called MUC19, originally from Denisovans, is unusually common in people with Indigenous American ancestry. This gene plays a key role in the immune system by producing mucins – proteins that form protective barriers in the respiratory and digestive tracts.

“In terms of evolution, this is an incredible leap,” said Fernando Villanea, assistant professor of Anthropology at the University of Colorado Boulder and lead author of the study. “It shows an amount of adaptation and resilience within a population that is simply amazing.”

The research reveals that one in three people with Mexican ancestry carry the Denisovan MUC19 variant, compared to just 1% of people with Central European ancestry. This pattern suggests natural selection favored the gene in the Americas.

Scientists found this variant in DNA from 23 ancient individuals at archaeological sites across Alaska, California, and Mexico, confirming it was present before European contact.

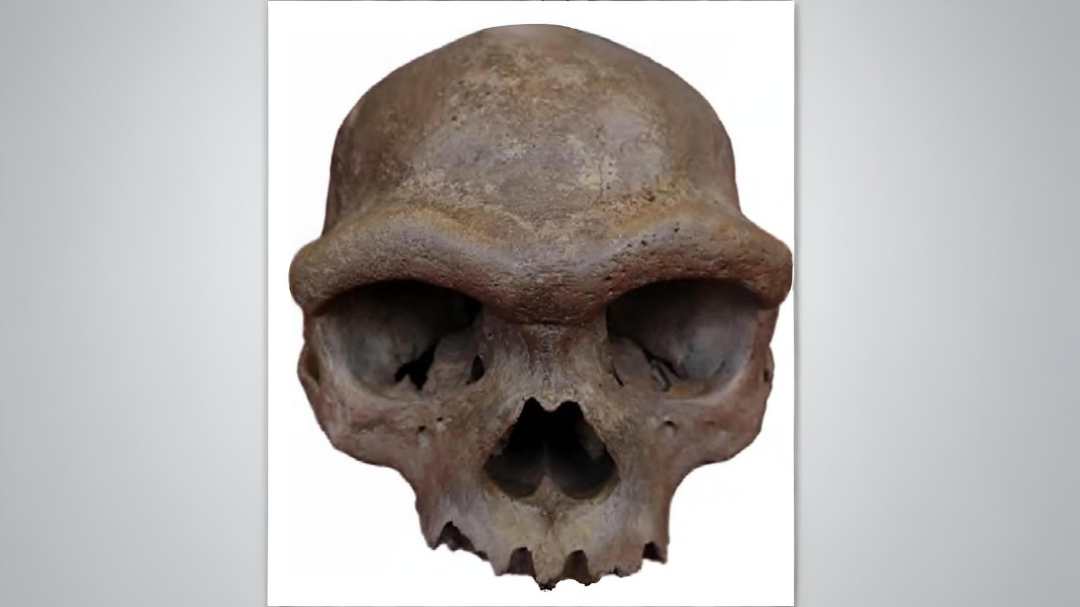

Denisovans, mysterious ancient relatives of humans, lived across Asia and went extinct tens of thousands of years ago. Despite limited fossil evidence, their genetic legacy continues through interbreeding with Neanderthals and humans.

The most surprising discovery was how this DNA reached humans. The researchers found that Denisovans first passed the gene to Neanderthals, who then passed it to humans – a genetic “Oreo” with Denisovan DNA in the middle and Neanderthal DNA on both sides.

Similar Posts

“This DNA is like an Oreo, with a Denisovan center and Neanderthal cookies,” Villanea explained.

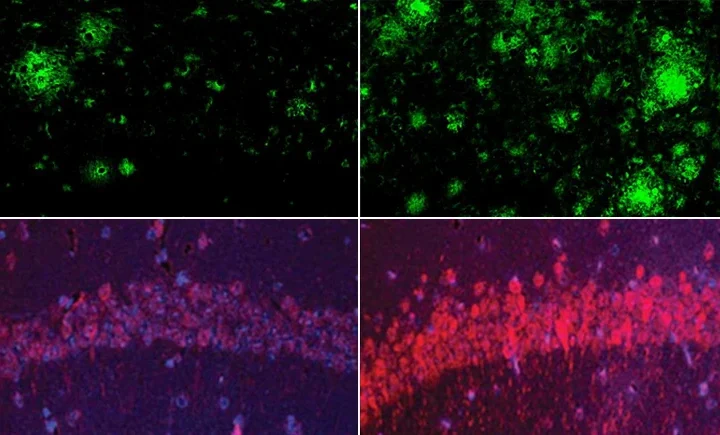

Why did this gene become so common in the Americas? The researchers believe MUC19 may have provided immune advantages against new diseases and environmental challenges. The gene contains an expanded section of repeated DNA sequences that could create “stickier” mucus – potentially improving defense against pathogens.

“All of a sudden, people had to find new ways to hunt, new ways to farm, and they developed really cool technology in response to those challenges,” said Villanea. “But, over 20,000 years, their bodies were also adapting at a biological level.”

This isn’t the first beneficial Denisovan gene identified. Another gene called EPAS1, which helps with high-altitude survival, spread among Tibetan populations.

Co-author Emilia Huerta-Sánchez from Brown University noted the importance of this genetic exchange: “Typically, genetic novelty is generated through a very slow process. But these interbreeding events were a sudden way to introduce a lot of new variation.”

The researchers plan to study how different MUC19 variants affect human health today, hoping to better understand its precise function.