Scientists have discovered that Spicomellus afer, the world’s oldest ankylosaur, was covered with massive spikes – some reaching up to a meter long. These spikes, fused directly to the dinosaur’s skeleton, reveal an extraordinary defense system unlike anything seen in any other animal, living or extinct.

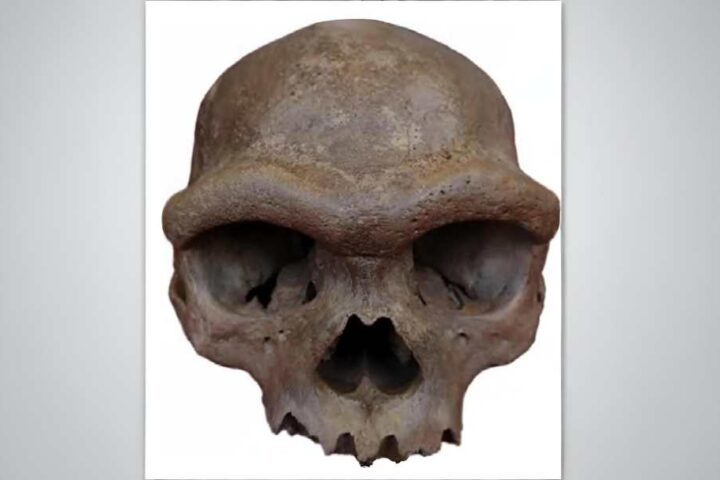

The remarkable findings, published in Nature on August 27, 2025, build upon the first description of this unusual dinosaur from 2021, which was based on a single rib bone. New fossil discoveries near Boulemane, Morocco, have unveiled the full extent of this Middle Jurassic creature’s bizarre armor.

“To find such elaborate armour in an early ankylosaur changes our understanding of how these dinosaurs evolved,” said Professor Susannah Maidment of the Natural History Museum, London, and the University of Birmingham, who co-led the research team.

Dating back 165 million years, Spicomellus afer is not only the oldest known ankylosaur but also the first ever found in Africa. What makes this dinosaur truly stand out is its unique bony collar ringed with huge spikes projecting from its neck.

The longest measured spike reached 87 centimeters – nearly three feet – and researchers believe they would have been even longer during the animal’s lifetime, covered with a keratin sheath similar to what covers modern animal horns.

“Seeing and studying the Spicomellus fossils for the first time was spine-tingling,” said Professor Richard Butler from the University of Birmingham. “We just couldn’t believe how weird it was and how unlike any other dinosaur, or indeed any other animal we know of alive or extinct.”

Perhaps most surprising was the discovery that Spicomellus had bony spikes fused directly onto all of its ribs – a feature never before seen in any vertebrate species. Its armor also included “huge upwards-projecting spikes over the hips, and a whole range of long, blade-like spikes,” according to Maidment.

Similar Posts

The research team believes this elaborate array of spikes likely served dual purposes – not just for defense against predators, but also for attracting mates and showing off to rivals. Interestingly, later ankylosaurs developed simpler armor that was primarily defensive in nature.

One explanation for this shift is that as larger predators evolved during the Cretaceous period, including bigger carnivorous mammals, crocodiles, and snakes, ankylosaurs needed more practical protection rather than flashy displays.

Another significant finding is evidence that Spicomellus had a tail weapon. While the end of its tail hasn’t been found, some tail vertebrae are fused together in a structure called a “handle,” which has only been found in ankylosaurs with tail clubs. This pushes back the timeline for tail weapon evolution in ankylosaurs by more than 30 million years.

The four-meter-long (13 feet) herbivore, weighing perhaps 1-2 tonnes, would have been a slow-moving plant-eater typical of ankylosaurs. The combination of a tail weapon and armored shield protecting its hips suggests that many key ankylosaur adaptations already existed by the time of Spicomellus.

The fossils were cleaned and prepared at the Department of Geology of the Dhar El Mahraz Faculty of Sciences in Fez, Morocco, where they remain catalogued and stored.

“This study is helping to drive forward Moroccan science,” said Professor Driss Ouarhache from Université Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah, who co-developed the research. “We’ve never seen dinosaurs like this before, and there’s still a lot more this region has to offer.”

The discovery not only changes our understanding of ankylosaur evolution but also highlights the importance of African fossils in reshaping our knowledge of dinosaur distribution across ancient continents.