Scientists have developed a breakthrough method to track exactly which breeding colonies of black-footed albatrosses are most affected when these seabirds are accidentally caught by fishing vessels.

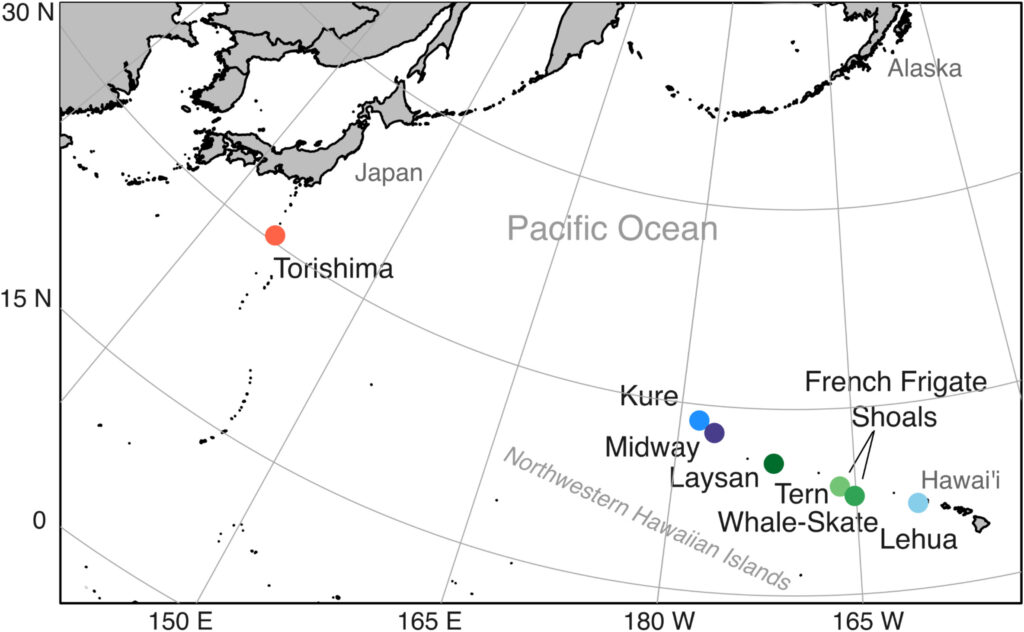

Using a technique called Genetic Stock Identification (GSI), researchers can now pinpoint the home colonies of albatrosses caught in fishing operations. This matters because these large seabirds breed on just a handful of islands but travel thousands of miles across the Pacific Ocean to feed.

“Genetic Stock Identification has been successfully used to study the movement of salmon populations. But it has rarely been applied to seabirds,” said Diana Baetscher, fisheries biologist at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center and co-lead author of the study. “Our study shows the benefits of this cost-effective and efficient genetic technology.”

The research analyzed 495 black-footed albatrosses caught in U.S. fisheries between 2010 and 2022. Scientists examined their genetic markers to trace each bird back to its breeding colony.

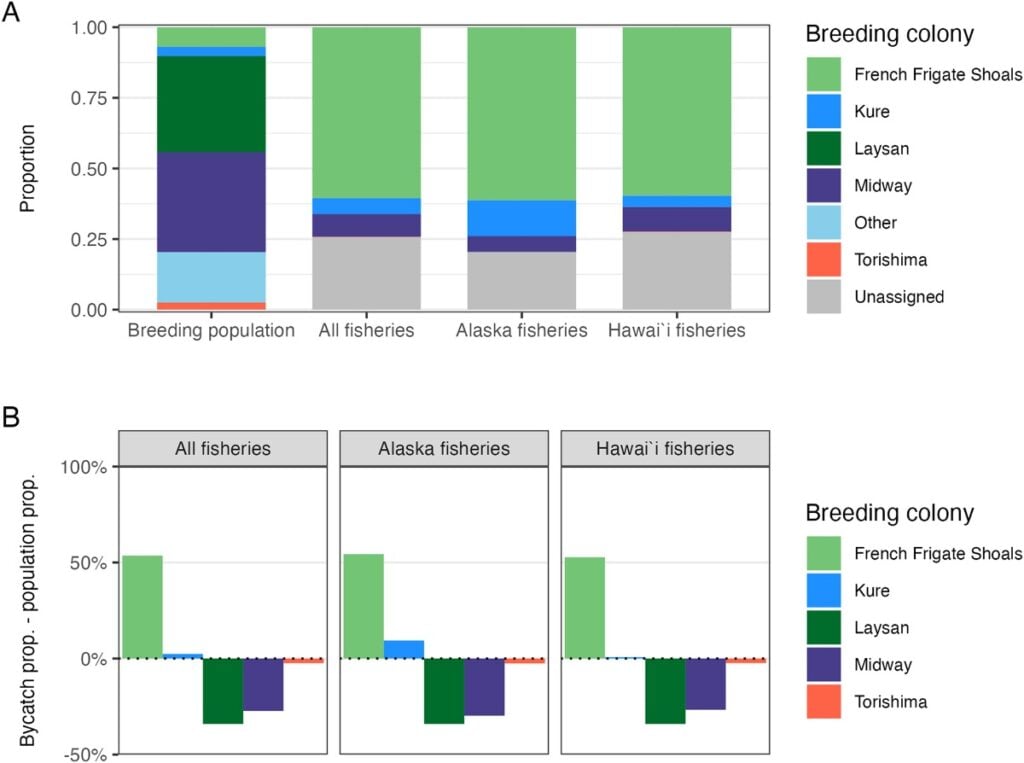

The findings revealed a surprising pattern: birds from the French Frigate Shoals in Hawaii were dying at much higher rates than expected. This small colony, which makes up just 7% of the total black-footed albatross population, accounted for 61% of birds caught in Alaska groundfish fisheries and 60% in Hawaii longline fisheries.

Meanwhile, birds from larger colonies at Midway Atoll (35% of population) and Laysan Island (34% of population) were caught much less frequently than their numbers would suggest.

Similar Posts

This discovery matters because black-footed albatrosses face multiple threats. They’re long-lived birds that reproduce slowly, having just one chick when they breed. While not endangered, they’re vulnerable to various dangers including invasive species, rising sea levels, disease, marine heat waves, and plastic pollution. Among these threats, fishing bycatch is the largest documented cause of death.

The research helps fill an important gap. Previous studies had found genetic differences between Japanese and Hawaiian albatross colonies, but little variation among the Hawaiian colonies where 97% of black-footed albatrosses breed. The new technique overcomes this challenge by examining differences across the whole genome.

“Black-footed Albatross only breed on islands,” Baetscher explains. “And there are a limited number of islands in their breeding range. It’s important to know if fisheries bycatch may be disproportionately impacting colonies at specific islands to help managers protect the species as a whole.”

Many U.S. fishing vessels already use bycatch prevention measures, like colorful streamers that scare birds away from fishing gear. However, some bycatch still occurs, and international fishing fleets may not follow the same practices.

The research provides valuable information for both NOAA Fisheries, which manages U.S. fishing operations, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which oversees seabird protection. With this data, they can develop more targeted conservation strategies for the most vulnerable colonies.

For the French Frigate Shoals population in particular, this research highlights the need for focused protection efforts as these birds face both fishing dangers at sea and the threat of habitat loss from rising sea levels and increased storm surges.