For the first time, researchers have identified specific electrical signals in the human brain that help us forget unpleasant memories. This breakthrough could lead to better treatments for conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety.

A team of scientists from Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) and Ruhr-Universität Bochum in Germany recorded brain activity in 49 epilepsy patients who already had electrodes implanted in their brains for medical treatment. The study, published in Nature Human Behaviour, reveals how our brains create “safety” signals when confronting previously frightening situations.

“The technique allows us to achieve a more detailed and mechanistic understanding of episodic memories, overcoming traditional approaches based solely on brain activation,” explains Daniel Pacheco-Estefan, the study’s lead author and researcher at UAB.

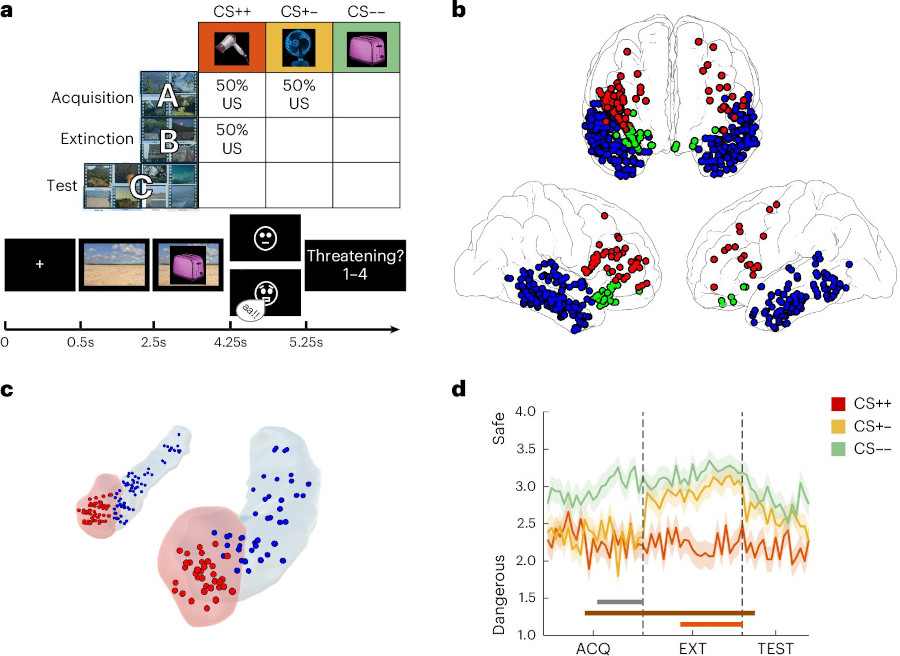

During the experiment, patients viewed neutral images like hair dryers, fans, and toasters. Some images were paired with an unpleasant sound. Later, researchers showed the same images without the sound to promote what scientists call “extinction” – the process where fearful responses fade away.

When viewing previously unpleasant images during the extinction phase, patients showed increased theta activity – a specific pattern of electrical brain waves – in the amygdala, a brain region central to processing emotions. This theta activity appears to signal safety, telling the brain “this is no longer dangerous.”

Interestingly, the brain created stronger connections between items that had previously been associated with negative sounds. “This result is consistent with previous research that has identified a generalised representational signature for unpleasant memories, which favours their involuntary reappearance in all kinds of situations in subjects who have undergone traumatic experiences,” notes Pacheco-Estefan.

The study also revealed why therapy gains sometimes don’t last. Safety memories formed during extinction are highly dependent on where they were created. This explains why fear often returns when patients leave the therapy setting.

“It seems that extinction memories are stored like memories of unique episodes – for the patient, the safe situation may be regarded as an exception that is unlikely to repeat,” says Nikolai Axmacher, coordinating researcher at Ruhr-Universität Bochum.

This finding helps explain a common problem in PTSD treatment: patients often improve during therapy sessions but experience setbacks in everyday life. The brain tends to view the therapy room as a special exception where safety rules apply, rather than generalizing that safety to other settings.

Similar Posts

The research builds upon previous work in mice that showed similar patterns in the amygdala and hippocampus, another key memory region. However, this study marks the first time these signals have been confirmed in the human brain.

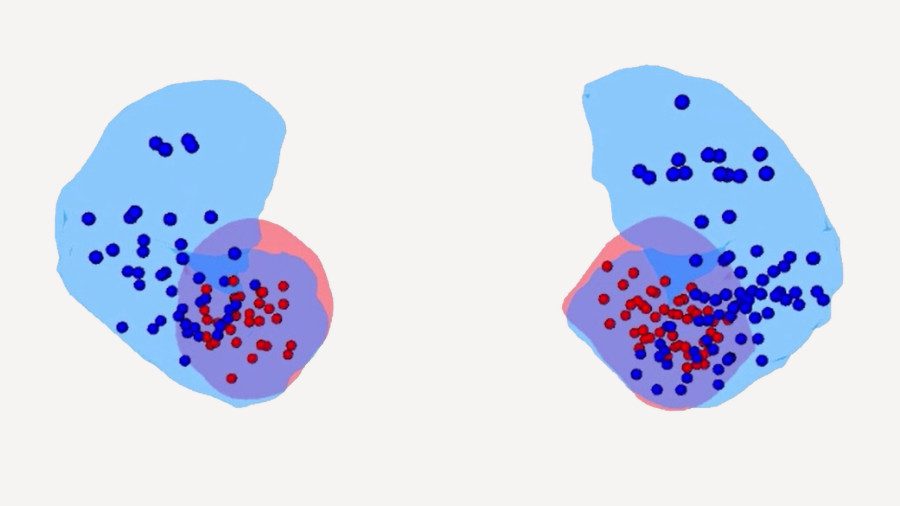

Researchers used a technique called Representational Similarity Analysis (RSA) to understand how brain regions represent and process information. This method allowed them to see not just which brain areas were active, but how those areas were encoding and storing memories.

The findings could inspire more effective treatments for anxiety disorders and PTSD by helping therapists understand how safety memories form and why they sometimes fail to generalize beyond the therapy room.

Current exposure therapies for PTSD and anxiety disorders already involve gradually facing feared situations in safe environments. This research suggests that varying the contexts during therapy sessions might help patients generalize their safety learning more effectively to real-world situations.

While promising, the research is still in early stages and hasn’t yet been translated into specific clinical protocols. Further studies will be needed to determine how these findings might be applied in treatment settings and with patients who don’t have implanted electrodes.