Extinct Plant Rediscovered After 58 Years Through Citizen Science Photo

Ptilotus senarius grows in such a remote part of Australia it’s a miracle it was rediscovered at all. Credit: Aaron Bean/iNaturalist

Citizen science platforms including iNaturalist are leading to major new discoveries and are becoming crucial to the work of scientists. How do we make them even better?

It took such a constellation of unlikely events syncing up, it’s almost unbelievable it happened at all.

Aaron Bean was banding birds on a sprawling outback station in a remote corner of northern Queensland when he spotted a plant that looked interesting.

A professional horticulturalist, Aaron snapped a couple of photos and, when he got back to phone reception, uploaded his finding to the vast citizen scientist database, iNaturalist.

As of January 2026, more than 290 million iNaturalist observations document life on Earth, with nearly 4 million observers contributing to the platform, making it one of the largest citizen science platforms in the world.

Once online, Aaron’s pictures found their way to a different Bean, Anthony Bean, an expert botanist from the Queensland Herbarium who immediately recognised the plant as something very special indeed: a presumed extinct plant not seen since the 1960s that he had described himself in 2014.

“It was very serendipitous,” says Thomas Mesaglio from the UNSW School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, who has written about the rediscovery for the Australian Journal of Botany.

“Aaron Bean is an avid iNaturalist user who opportunistically took some photos of a few plants that were interesting on the property.”

The Incredible Journey of Ptilotus Senarius

From extinction to rediscovery: A timeline of remarkable events

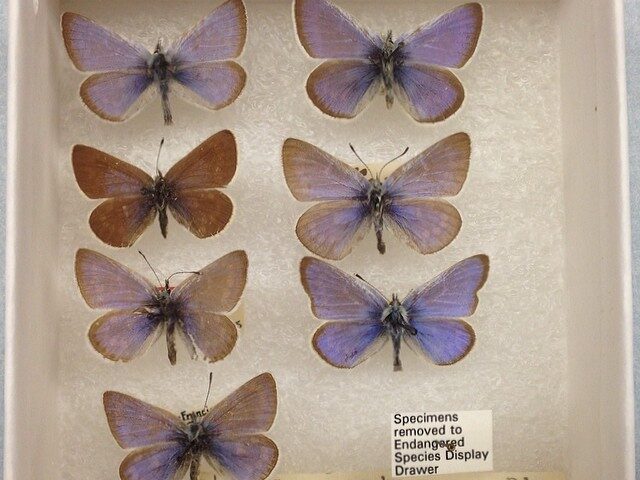

Ptilotus senarius was last collected in the wild near the Gulf of Carpentaria. The small, slender shrub with distinctive purple-pink flowers that look like an exploding firework with feathers then vanished from scientific records. It was presumed to be one of the hundreds of plant species that have gone extinct in the wild internationally since the 1750s.

Tony Bean, a Senior Botanist at the Queensland Herbarium, formally described Ptilotus senarius using two unidentified specimens collected in 1925 and 1967. The conclusion: cattle grazing pressure likely contributed to its disappearance from the wild.

Horticulturalist Aaron Bean was working on a private property in the Gilbert River region when he “opportunistically” photographed a few plants while banding birds. He snapped photos and uploaded them to iNaturalist when he regained phone reception.

“Serendipitously, we had another Bean,” explained Thomas Mesaglio. Tony Bean, browsing that plant group on iNaturalist, immediately got excited when he saw the photo and messaged Mesaglio. The race was on to collect a specimen before it stopped flowering.

With the help of a cooperative land owner, a specimen was collected from the property. “Tony messaged me on July second, and we had a specimen collected on the seventh,” Mesaglio said. “Then, within another week, it had been mailed to Brisbane and checked.”

The rediscovery was confirmed and published in the Australian Journal of Botany. Ptilotus senarius moved from “extinct” to “critically endangered” on Queensland’s threatened species list, opening doors for conservation efforts and scientific protection. Only around 15 plants were observed, requiring targeted surveys to determine if it survives elsewhere.

A Chance Find

Ptilotus senarius is a small, slender shrub with pleasing purple-pink flowers that look a bit like an exploding firework with feathers.

It’s found only in a band of rough country near the Gulf of Carpentaria, and hadn’t been collected since 1967. According to a study by Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Stockholm University, at least 571 plant species have been documented as extinct since 1750, though the actual number is likely higher.

But with Anthony and Aaron Beans’s keen eyes, and a land-owner willing to gather a specimen, Ptilotus senarius is now confirmed to still be hanging on, and actually recently moved onto Queensland’s critically endangered species list where scientists and conservationists can help it.

“It’s one of these situations where everything had to fall into place and there was a bit of good fortune involved,” says Mesaglio.

It’s just the latest example of an emerging trend: citizen scientists snapping pictures of plants and animals they come across, uploading them to databases like iNaturalist, only to learn they’ve stumbled upon something we thought was lost, or else is completely new to science. Similar citizen science efforts recently helped locate extinct oak trees in Texas and rediscover presumed extinct species globally.

Opening Up Private Land

iNaturalist is becoming an invaluable resource to people like Thomas Mesaglio who, constrained by the vastness and diversity of a place as big as Australia, can’t be everywhere.

And given that freehold land covers around 30 per cent of the Australian continent, often scientists have difficulty accessing many areas in the first place. Around 60 per cent of Australia is privately owned or managed when including leaseholds and other private tenures, and researchers often struggle to access many of the most ecologically important sites.

“If you are the property owner or you’re someone who has permission from the owner to be there then suddenly it opens up this whole new world,” Mesaglio says.

With the help of a cooperative land owner, scientists were able to examine a specimen and confirm the identity of Aaron Bean’s find. Credit: Aaron Bean/iNaturalist

The Power of Citizen Science on iNaturalist

Making These Databases Even Better

Scientists want to make these databases even better by getting more members of the community involved and taking high-quality, data rich pictures, and most crucially they want more landowners to do the same.

For example, in New South Wales, the Land Libraries project run by the state government’s Biodiversity Conservation Trust provides equipment and training to landowners in how to document the biodiversity on their properties and upload it to citizen science platforms.

Mesaglio is supportive of these programmes and wants to see them expanded not just because it gives him digital access behind the fences of private properties, but because more people using these tools has a conservation benefit in and of itself.

“Engaging landholders themselves with science and the natural world and getting them more passionate about diversity makes them far more likely to be interested and invested in protecting that diversity,” Mesaglio says.

It’s one of these situations where everything had to fall into place and there was a bit of good fortune involved. But it’s actually clinging on by its fingertips.

How to Contribute to Scientific Discovery

Every observation counts—here’s how to make yours valuable

Take Comprehensive Photos

For people interested in using iNaturalist for the first time, Mesaglio says to be most useful to scientists you need to provide as much information about your observation as possible. A close up of a flower might not provide enough information if that flower is from a group of dozens of different plants with similar looking flowers, but taking many pictures of other features as well, such as the entire plant, bark and the leaves, can provide a lot more information.

Record Additional Details

Mesaglio also wants people to record that extra bit of information that might not necessarily be visible in a photograph, things like soil type or what other plants are growing nearby, or if it had pollinators visiting. Even attributes like plant smell can give scientists vital clues about a plant’s identity, Mesaglio says. “The more information you can provide and the more context you can provide, the more potential uses that that record will have in the future.”

Upload and Connect

Share your observations on iNaturalist when you have internet access. The platform connects your photos with expert identifiers worldwide, potentially leading to discoveries of new species or thought-extinct plants clinging to survival, as this case proved.

Improving the Dataset

In separate research, Mesaglio found iNaturalist had been cited in papers covering 128 countries and thousands of species, underscoring how important the resource has become.

With more finds uploaded every day, and the quality of the data improving, Mesaglio knows there are even more discoveries waiting to be found.

The rediscovery of Ptilotus senarius after nearly 60 years was discussed in research published by UNSW scientists. The platform’s data now supports nearly 7,000 scientific papers and has matured into a global data ecosystem since its founding in 2008 as a UC Berkeley project, later adopted by California Academy of Sciences and National Geographic Society.

The Growing Power of Citizen Science Data

The Broader Conservation Impact

The researchers say the rediscovery demonstrates the growing power of citizen science data in research and conservation.

“Now suddenly, you’ve got people across the whole country who could record something,” Mr Mesaglio said. “We can massively expand our eyes and ears across the country (and) it facilitates this orders-of-magnitude increase in the sheer volume of data collected.”

Discoveries from regular citizens are often able to capture observations from hard-to-reach places, publish data instantly and connect it with expert identifiers worldwide. This approach has helped document rare species in India and supports global biodiversity conservation efforts.

The 1960s: A Time of Discovery and Loss

The 1960s were a time when many animals and plants were documented and then lost. The last time Ptilotus senarius had been seen before its rediscovery was 1967.

It was that same year that New Zealand’s South Island kōkako was officially seen for the last time. And it was just two years later that the Victorian grassland earless dragon was last documented before its shock rediscovery in 2023.

In these post-war years, investment in Australia’s environment was flowing again, after cutbacks during the two world wars. But over the following six decades native species have been under severe pressure. The nation’s population has boomed, and there has been widespread destruction of habitat combined with pressure from invasive species, disease, and climate change.

According to data collected by the Invasive Species Council, there have been approximately 21 animal extinctions documented in Australia since the 1960s. This makes rediscoveries like Ptilotus senarius particularly significant in the context of ongoing extinction threats.

Looking to the Future

Mr Mesaglio hopes scientists, conservationists and the public will increasingly use databases such as iNaturalist to rediscover lost species and monitor the ranges of known species.

“People can be curious about the natural world, to photograph things they come across …. you never know how significant it might be,” he said.

“Rediscoveries offer that opportunity to conduct follow-up, targeted surveys and consistent long-term monitoring to give us a better understanding of exactly where and how these species are distributed across the landscape,” he said.

The next time you’re outdoors, photograph what interests you. Upload it to iNaturalist. You might contribute data that helps scientists understand species distributions, climate impacts, or—like Aaron Bean—you might rediscover something thought lost forever. Technology like AI is already being used alongside citizen science to accelerate conservation efforts.

The Discovery That Almost Didn’t Happen

The location of the find is being kept confidential. “The last thing we want is a million people turning up and trying to get onto private property to see this plant,” Mesaglio said.

We need to figure out if this is the only population, and if there are tens of plants, hundreds of plants or thousands of plants. The team was determined to collect an example of the plant before it finished flowering, as its blooms are the most distinct component.

Mesaglio described this as one of a series of “very serendipitous series of events” that led to the plant’s rediscovery. While exploring the property, horticulturalist Aaron Bean had opportunistically taken photos of some “very interesting looking plants”. When he uploaded the photos, Bean identified the plant’s genus, but there are over 120 species in Australia, and he wasn’t sure which one it was.

His images on iNaturalist caught the eye of Tony Bean, who coincidentally shares the same surname. It was his enthusiasm about the plant that escalated the race to identify it.

The rediscovery was confirmed with a paper published by CSIRO Publishing in the Australian Journal of Botany. iNaturalist is a free website used by millions of people worldwide. In June 2025, the platform reported its global community had helped identify the species of plants and animals in 250 million verifiable observations.

The Queensland Herbarium confirmed the plant’s identity after specimens were collected from the property. The species now appears on official biodiversity databases including the Atlas of Living Australia, where its conservation status can be monitored.

Citizens interested in participating can access training through programs like New South Wales’ Land Libraries project, which provides equipment and guidance for documenting biodiversity on private properties.

Aaron Bean’s observation remains accessible on iNaturalist’s public database, where it continues to contribute to scientific knowledge about the species’ distribution and habitat requirements. The platform allows anyone with a smartphone to document and share observations with the global scientific community, potentially contributing to future conservation discoveries like this remarkable find.